In the first of this series of blogs I discussed the importance of good explanations in teaching and the potential benefits of good-quality textbooks. Here I explore how good quality curriculum and teaching resources, including textbooks, might be developed.

Curriculum development

Curriculum and curriculum-making exist at different levels. Deng (2020) describes different levels of curriculum. The ‘policy curriculum’ is the ideal or abstract curriculum. The ‘programmatic curriculum’ is then the technical or official curriculum as described by operational documents such as syllabi and course specifications. The policy and programmatic curricula together form the ‘institutional curriculum’ which sets out the expected teaching and learning within the education system. This is normally organised into an array of school subjects as a means of operationalising the curriculum. However, there is also the ‘classroom curriculum’ which is what is actually enacted in classrooms. Teachers are largely responsible for the classroom curriculum, and this depends on how they transform the institutional curriculum into teaching and learning activities with a group of pupils. The teacher is the mediator of the instructional core in their classroom and how learners interact with the subject matter being taught. Teachers may work individually and have significant autonomy over their classroom curriculum or may work in school or departmental teams where this is decided more collaboratively, but even if a curriculum is ‘presented’ to a teacher to implement, every teacher has significant autonomy and control over what actually happens in their classroom.

The institutional curriculum, in the form of a national curriculum framework is only, and I would argue should only, provide the broad outline of the curriculum content expected. To specify more at this level would result in a very centralised, top-down and unwieldy curriculum. Nevertheless, a curriculum framework should be specified in sufficient detail and with sufficient clarity to provide teachers with good guidance on what learners should ‘know’, ‘do’ and ‘understand’. This is something the Scottish Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) Experiences and Outcomes fail to do as was concluded by the OECD when it reviewed CfE in 2021 (LTS, 2009; OECD, 2021).

The production of national curriculum guidance, including the syllabi for different subjects, is non-trivial and needs to be done by bringing together teams of people with the right range of expertise. No one person can be expert in all areas required and it is through the bouncing of ideas off each other in such a team that different perspectives can be recognised and addressed and thereby producing better curriculum guidance than any one person can do alone. I experienced this myself when a member of the Higher Still Specialist and Reference Groups for Physics in the late 1990s. Not that we were allowed to produce the curriculum and assessment frameworks we wished. There was always pressure from ‘higher up’ for us to do things, particularly in relation to the assessment, in a way we considered would be unworkable in the classroom. I also wish I could be more precise with my use of the term ‘higher up’ but I have never been able to find out who was actually responsible for the decisions. If expert groups are formed to produce programmatic curriculum documents, it is important that their views are then actually listened to.

National curriculum development teams need to include a range of expertise, including practitioners from the classroom who understand learners and the realities of teaching. However, such teams also need to have others from the likes of universities and learned societies who have had time that busy classroom teachers have not likely had to think about curriculum matters and have knowledge of research on curriculum-making in a way teachers do not. The development of assessment also needs to be considered alongside the development of curriculum; it should not be a ‘bolt-on’ at the end. Every major curriculum development which has taken place in Scotland during my career, including Standard Grade, Higher Still and Curriculum for Excellence, has resulted in assessment and certification proposals that have been overly complex and bureaucratic and within a year or two of their introductions they have had to be simplified. A proper, and realistic, account must be taken of assessment and any related certification from the outset during any curriculum development process. Regardless of the curriculum and its assessment, due to accountability pressures there will be an inclination for teachers to ‘teach to the test’. It is therefore important to consider the types of ‘tests’ from the outset to ensure they have as little unintended washback on the curriculum and teaching and learning as possible. A common format of assessment is also never going to fit-for-purpose across all subjects, topics, and skills. However, even if there is a well-developed national curriculum and assessment framework, teachers must make many local curriculum-making decisions when deciding on what ought to happen in their classrooms, and when, how, and by whom.

Research-based resource development

My interest in that there must be a better research-based approach to developing curriculum guidance and associated teaching materials, compared to those approaches I had experienced myself, was piqued by a talk at the GIREP conference in Dublin in 2017 (GIREP, n.d.). Claudia Haagen-Schützenhöfer from Austria described a project where the materials for teaching basic optics in secondary schools were developed through seven iterative cycles over several years where they were used, evaluated and refined each time based on the research data gathered (Haagen-Schützenhöfer, 2017; Haagen-Schützenhöfer & Hopf, 2015). Here was an example where curriculum development appeared to be properly evaluated and researched. Over an extended period, the curriculum materials and an understanding of the pupil learning taking place was gradually improved and the approach to teaching perfected. It illustrated what could be done if there was a will to prioritise such work.

A few interactions with physics teachers from Japan have led me to believe that such gradual evolution and improvement of teaching materials and the professional understanding of the underpinning curriculum, based on high-quality collaborative research and evidence informed practices, is commonplace in that country. This would certainly be consistent with their collaborative approach to professional learning and the use of lesson study which was first developed there and is practised widely in Japan (Lewis et al., 2006).

Alongside this, I have become increasingly intrigued by the work of Zig Englemann and the development of Direct Instruction materials since Project Follow Through in the USA in the 1960s and 1970s. This is in terms of both trying to understand the development process used for the Direct Instruction materials but also why, despite the strong research evidence of the effectiveness of the approach, it has largely been ignored. Project Follow Through was a comparative research study of different instructional methods, one of which was Direct Instruction. Hundreds of thousands of primary aged pupils were involved and Direct Instruction proved to be the method with by far the greatest impact. The Direct Instruction approach is well-described by Kurt Englemann, Zig’s son, in his recent book (Englemann, 2024), which was some recent holiday reading for me. The story of the repeated ignoring and dismissal of Direct Instruction for the effective teaching of reading and mathematics in the early years of primary education is a salutary one, and one which shows that opinion and dogma can easily outweigh strong research findings (Mason & Otero, 2021; Stockard et al., 2020). Even although Direct Instruction has been largely ignored by the educational establishment, if teachers had had more time and opportunity to engage with research it might have had a chance to have become better known.

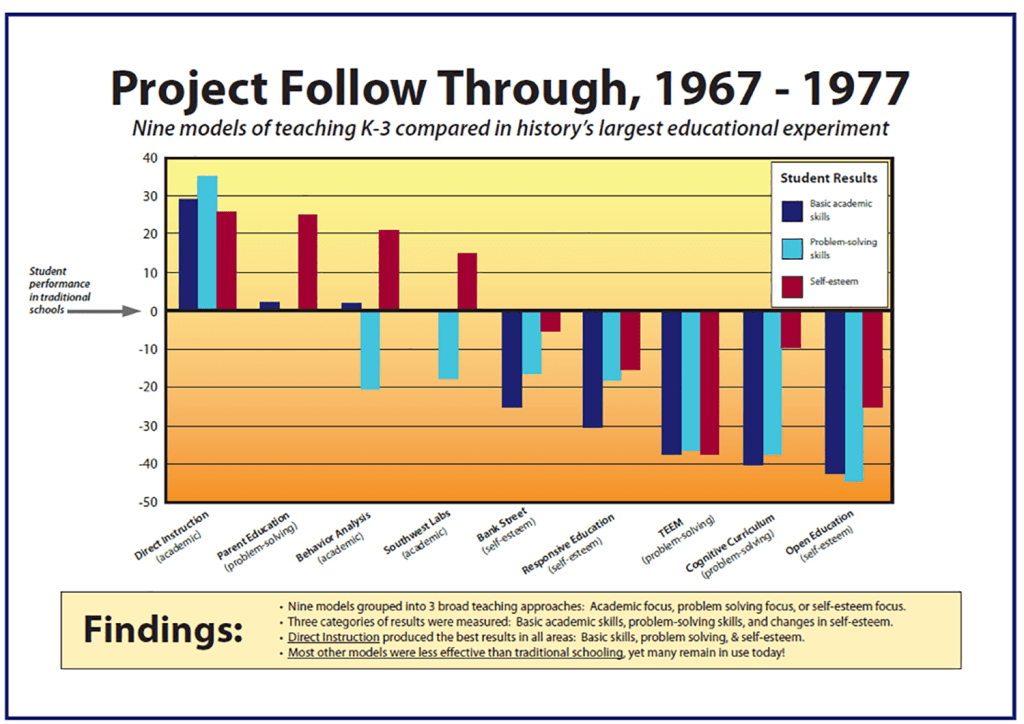

If you would like to see the impact that teaching using Direct Instruction materials and methods can have, I strongly recommend you watch Zig Englemann with a group of six and seven year olds from some of the most deprived neighbourhoods of Chicago at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j9SjFsimywA. The film is old and grainy and the audio quality not brilliant, but to see young primary age kids factorising and solving simultaneous equations is worth giving up half an hour of your time and watching all the way through (Association for Direct Instruction, 1966). Direct Instruction impacts very positively not only on the basic skills of the learners but also their problem-solving capability and, perhaps most importantly the affective domain such as their self-esteem. Direct Instruction impacted pupils’ self-esteem much more than any of the teaching approaches with which it was compared, and which were specifically promoted as, or designed to, develop the self-esteem of the pupils as the chart below illustrates. I think the behaviour of the kids in the video also provides good evidence that this is the case.

Figure: The results of Project Follow Through

I was also impressed by Darren Leslie’s work when he spoke about his use of Direct Instruction at researchED Aberdeen in 2022. He described how he had used a Direct Instruction mathematics programme (McGraw Hill, 2004) with the weakest S1 mathematics classes in Bell Baxter Higher School in Fife (the secondary school I attended). The pupils made the equivalent of around four years of progress within just a few months and were then able to move into ‘mainstream’ maths classes in S2. It begs the obvious question, when much store is placed by politicians and others on closing the poverty related attainment gap, why such proven methods, which were first developed a half century ago are not more widely used, or even known about by many teachers or teacher educators, especially as there is strong evidence that such methods help the most disadvantaged the most.

I think an important part of the Direct Instruction story, and why it links with Haagen-Schützenhöfer’s work I described above, is that all the Direct Instruction materials have gone through iterative development cycles. Draft materials were tested in classrooms and good research and evaluation data gathered and used to improve the materials. Only when the materials had been well tested through such ‘field-trials’ were they then published, and even then, subsequent editions have been further improved. This is not something which has occurred with any curriculum developments in Scotland in recent decades.

I suspect the main reason Direct Instruction materials are not more widely adopted is that they use scripted lessons. There is a widespread view that teachers, as professionals, ought to be able to adapt their teaching to the needs of the learners and following a scripted lesson would appear to rail against this. Many argue that the approach also diminishes the autonomy and agency of teachers. I agree that following such a directed approach does reduce the autonomy of teachers, but it is important for the progression and continuity of the learning of young people that all teachers work within an agreed curriculum framework and use similar approaches. I think that often the term autonomy is confused with agency. I think that working within a fairly tightly bounded curriculum framework whilst restricting autonomy does not necessarily restrict teacher agency, and the same can be said in many respects for a pedagogical framework also. Doing so may actually free teachers up to focus on other aspects of teaching and learning and thereby allowing them to demonstrate a high level of transformative professionalism and better meet the needs of all their learners.

The story of why Englemann ended up with scripted lessons is an interesting one. Englemann’s background was in marketing and not in teaching or education. He initially looked towards educational research to find out how many times someone needed to be exposed to a message before they would likely remember it and was surprised that no such research about learning existed. He then started to conduct his own experiments and subsequently moved into the field of researching and developing materials for teaching basic reading and mathematics based on his findings. Through this process he developed the methods underpinning Direct Instruction, however, when he then tried to get teachers to use these methods by supplying them with the underpinning guiding principles, he found they deviated from them diminishing the impact of the approach. To ensure fidelity in the methods, and therefore in the pupil outcomes, he was in effect driven to produce scripted lessons for teachers to use as the precise use of language in explanations is crucial to their effectiveness. However, the use of the materials was always backed up with professional learning to help ensure that the teachers understood the rationale for and underpinning principles of the Direct Instruction approach. The importance of this professional learning was described by Darren in his talk at researchED Aberdeen.

Any significant curricular or pedagogical change in education will only be successful if the rationale for it is understood and accepted by the teaching profession and sufficient time is devoted to high-quality professional learning. This needs to be matched with opportunities to embed the change in practice in order to ensure that the change becomes a habit, if not, teachers will quickly return to previous behaviours (Hobbiss et al., 2020).

In the next part of this series, I will consider autonomy and teacher agency and how this links to teacher professionalism and curriculum reform.

References

Association for Direct Instruction. (1966). Direct Instruction Archive – Arithmetic – YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j9SjFsimywA

Deng, Z. (2020). Knowledge, Content, Curriculum and Didaktik: Beyond Social Realism. Routledge.

Englemann, K. E. (2024). Direct Instruction: A Practitioner’s Handbook. John Catt.

GIREP. (n.d.). Group International de Recherche sur ’Enseignement de la Physique – Internaltional Research Group on Physics Teaching. Retrieved 30 July 2024, from https://www.girep.org/

Haagen-Schützenhöfer, C. (2017). Development of research based teaching materials: The learning output of a course for geometrical optics for lower secondary students. Springer Proceedings in Physics, 190, 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44887-9_9/FIGURES/3

Haagen-Schützenhöfer, C., & Hopf, M. (2015). Design-based research as a model for systematic curriculum development: The example of a curriculum for introductory optics. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 16(2), 020152-1-020152–24. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.16.020152

Hobbiss, M., Sims, S., & Allen, R. (2020). Habit formation limits growth in teacher effectiveness: A review of converging evidence from neuroscience and social science. Review of Education. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3226

Lewis, C., Perry, R., & Murata, A. (2006). How Should Research Contribute to Instructional Improvement? The Case of Lesson Study. Educational Researcher, 35(3), 3–14. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242574847_How_Should_Research

_Contribute_to_Instructional_Improvement_The_Case_of_Lesson_Study

LTS. (2009). Curricum for Excellence: Sciences – Experiences and Outcomes. https://education.gov.scot/Documents/sciences-eo.pdf

Mason, L., & Otero, M. (2021). Just How Effective is Direct Instruction? Perspectives on Behavior Science, 44, 225–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-021-00295-x

McGraw Hill. (2004). Corrective Maths | Numeracy Programs | McGraw-Hill. https://www.mheducation.co.uk/schools/secondary/direct-instruction/corrective-mathematics

OECD. (2021). Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence: Into the Future, Implementing Education Policies. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2021/06/scotland-s-curriculum-for-excellence_9de88365.html

Stockard, J., Wood, T. W., Coughlin, C., & Khoury, C. R. (2020). All Students Can Succeed: A Half Century of Research on the Effectiveness of Direct Instruction. Lexington Books.

Leave a reply to Improving education – curriculum, explanations, professionalism and more – Part 4 – Stuart Physics Cancel reply