Every now and again amongst Scottish physics teachers the topic of why electron flow rather than conventional current is commonly used to teach electric circuits flares up. This post is a summary of some investigations I made to try and find out what might sit behind that decision.

Probably the last person who could have shed some more accurate illumination on the matter, Jim Jardine, died earlier this year just shy of his 100th birthday. Unfortunately, I didn’t make the opportunity to ask him when he was alive, so I suspect we will never get a definitive answer to the question. Therefore, what follows involves a bit of conjecture on my part based on what I could find from an analysis of syllabus documents and textbooks.

The decision to use +1 coulomb as the basic unit of charge was made many decades ago before our more detailed knowledge of subatomic structures was known. It is probably just unfortunate that in 1897 J. J. Thompson discovered the electron had what had already been defined as a negative. Afterall it would have been a 50:50 decision. All the conventions of electricity and magnetism are based on the use of positive charge, such as the definition of electrical potential and the directions of arrows on circuit symbols like diodes and transistors.

However, since I was a school pupil myself in the 1970s, and a teacher since the 1980s, it has been common practice for physics teachers in Scotland to teach about electric currents in electric circuits using electron flow rather than conventional current, i.e., negative charges moving from negative to positive rather than positive charges moving from positive to negative. But what led to Scottish school physics education going down the electron flow route when everywhere and everyone else stuck with conventional current?

I had put it down as an outcome of the very significant discussions about the nature of science education and subsequent curriculum development that took place in the 1960s, in much of the western world, initiated at least partly because of Sputnik being launched by the USSR.

Although I have no direct evidence, I assume that conventional current was likely to have been used prior to the 1960s. As I see it, in the 60 or more years since then, there have been four significant periods of curriculum development in Scottish Physics education.

1960s

This was when there was the development of the Alternative Ordinary Grade and Higher Grade syllabi and the introduction of the Certificate of Sixth Year Studies (CSYS). I would also include the developments that occurred following the publication of Curriculum Paper 7 in 1969 and which led to the likes of Science for the 70’s and the Scottish Integrated Science project. The Alternative O Grade developments ran in parallel and overlapped with the Nuffield curriculum changes south of the border. Jim Jardine had a big hand in both of these and there were many significant changes, especially in practical work from which we still benefit.

1980s

Standard Grade and its applications based approach and the tweaks to Higher and CSYS that followed. This did a great deal for the popularity and uptake of Physics and of course Jim also led the committee that developed the Standard Grade Physics course.

1990s

Higher Still where the mantra was “minimum change”, so the physics did not change as much as it perhaps needed to, but we got unit assessment as well as course assessment and Advanced Higher replaced CSYS. (Rightly or wrongly, I am ignoring 5-14 as not having much impact on the physics curriculum.)

2010s

CfE (and the Revised Higher and Advanced Higher courses immediately before) where we have had a welcome refresh of the physics in the Senior Phase but the imposition of an unsuitable assessment regime with ramifications that have rumbled on to 2023 and show no signs of abating.

The move to the orthodoxy (I had better not use the term convention) of using electron flow seems to have been pretty much in place during my own education in the 1970s and certainly by the time I started my PGCE in 1983. Hence my assumption that it was one of the products of the developments around the introduction of the Alternative syllabuses of the 1960s alongside the development of new and innovative equipment for practical work like tartan trolleys and ticker tape, the Westminster electromagnetism kits, Teltron tubes, and much else we have become very familiar with since.

I have done a bit of digging into my archive of publications to see what further clues I can find, but my hypothesis is that the shift occurred not so much with statements in published curriculum documents but in textbooks and likely in professional development events and other activities associated with the implementations of the new courses, or even Jim influencing several generations of student teachers at Moray House.

Here is what I have found.

Curriculum Documents

Scottish Certificate of Education Examination Board (SCEEB, and one of the predecessors of the SQA responsible for national examinations such as Higher). The First Cycle for S1/2 [which overlaps with the physics content of Curriculum Paper 7 (1969)], Second Cycle – Ordinary Grade, and Third Cycle – Higher Grade syllabus (1969) and its update (1976).

There is no mention of direction of electric current. It only contains brief statements such as:

p37 Magnetic field of straight wire carrying current.

p37 Force on conductor (qualitative).

The Scottish Curriculum Development Service (SCDS, and a predecessor of Education Scotland) Memorandum 31 Specific Objectives for Ordinary Grade Physics (1977)

There is no mention of direction of electric current. This document provides more specific statements interpreting the short and somewhat vague contents of the SCEEB Second Cycle syllabus published in 1976. It contains the sorts of statements we would become accustomed to seeing in future course arrangement and specification documents, such as:

Pupils should acquire the ability to

5. recall that the direction of the force on a current-carrying conductor in a magnetic field depends on the directions of the current and the field (p16)

The Standard Grade Arrangements in Physics published by the Scottish Examination Board in 1988 contains the following Learning Outcomes for the Using Electricity unit at General Level (p21):

Pupils should be able

6. to state that electrons are free to move in a conductor

7. to describe the electric current in terms of the movement of charges around a circuit

It would appear that there was no definitive preference for either conventional current or electron flow in any of the syllabus document and there does not even appear to be an acknowledgement that two options might exist, although it might be reasonably implied from the two Standard Grade Learning Outcomes that a current is a movement of electrons.

Textbooks

Jim Jardine’s Physics is Fun Book 2 (1964)

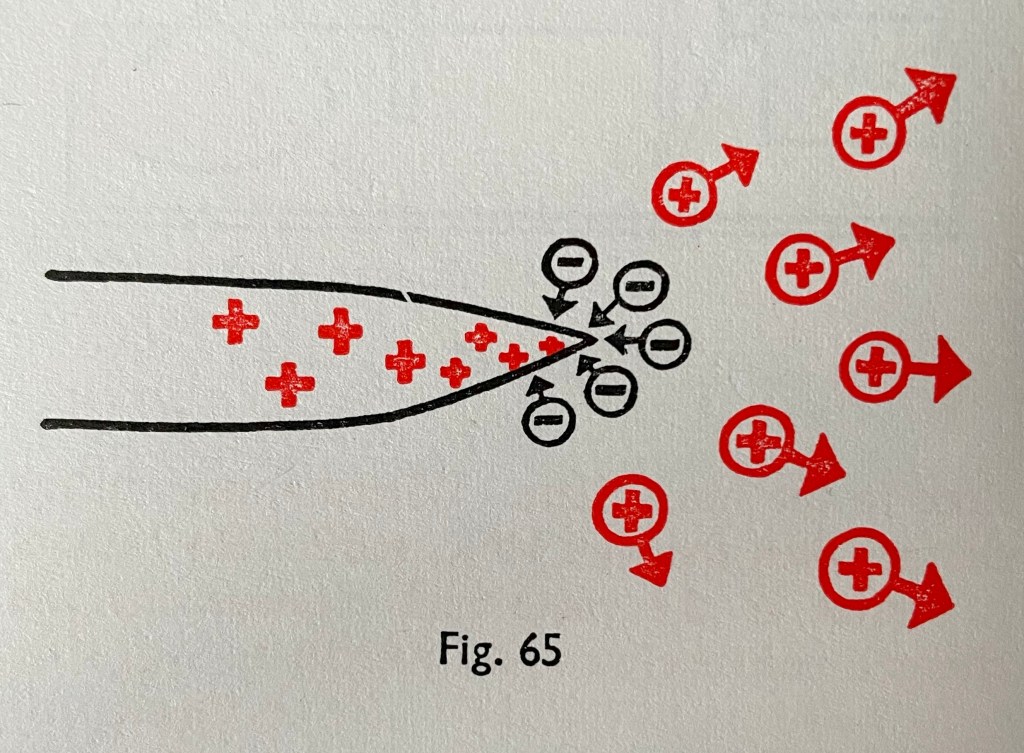

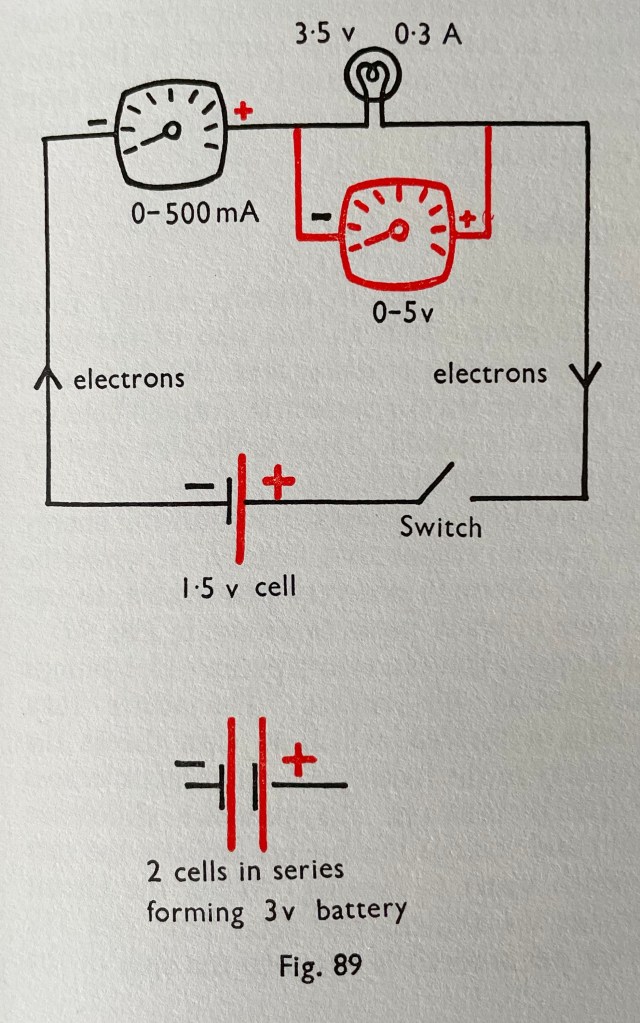

Movement of charges, electrons, and ions, is well covered in chapter 2 from p15 but the first signs of electron flow being interpreted as a current appear on p37 in a section titled “Direction of Current”. “An electric current can be considered as a flow of negative charges (electrons) in one direction or a flow of positive charges in the opposite direction. We will usually represent it as a flow of electrons, particularly when dealing with electric current in wires. Black arrows will then be used to indicate flow of electrons. When dealing with the movement of positive charges arrows will be coloured red.”

Figure 65 is an illustration of positive and negative charges represented in this two colour manner.

Figure 89 then shows a circuit with black arrows on the wires labelled electrons indicating a current in the circuit.

In Physics is Fun Book 4 (1967) p58 the section uses black print to show streams of electrons in the case of magnetic fields around conductors.

NatPhil ‘O’ (1973)

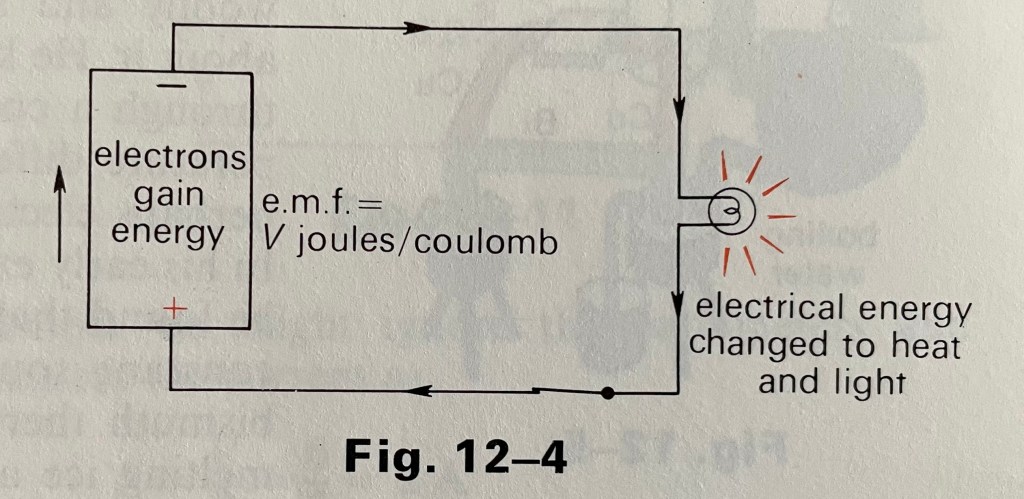

Jim continues to use the black and red two colour approach but there is definitely less of the red and in figures such as figure 12-4 on p109 it would be very easy just to interpret a current flowing negative to positive and to lose the distinction very clearly made in the Physics is Fun books.

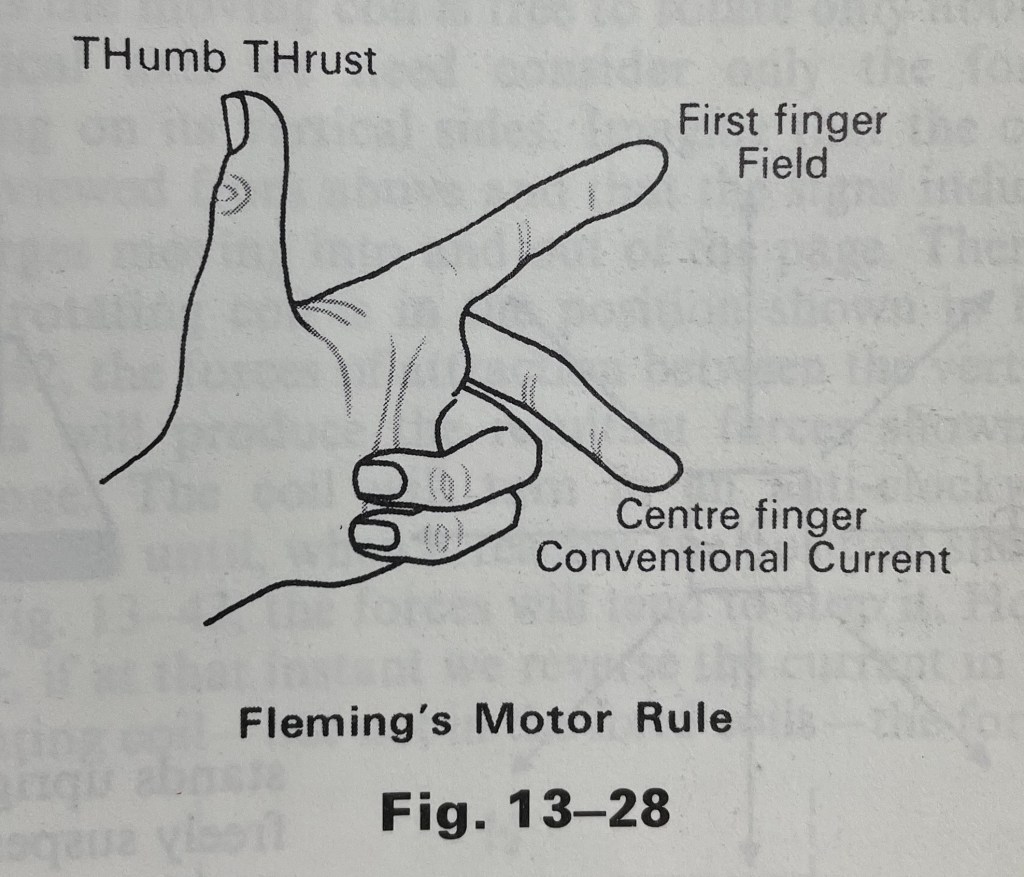

However, on p120-1 in the magnetism section reference is made to both positive charges and electrons and figure 13-28 is of Fleming’s Motor Rule using conventional current.

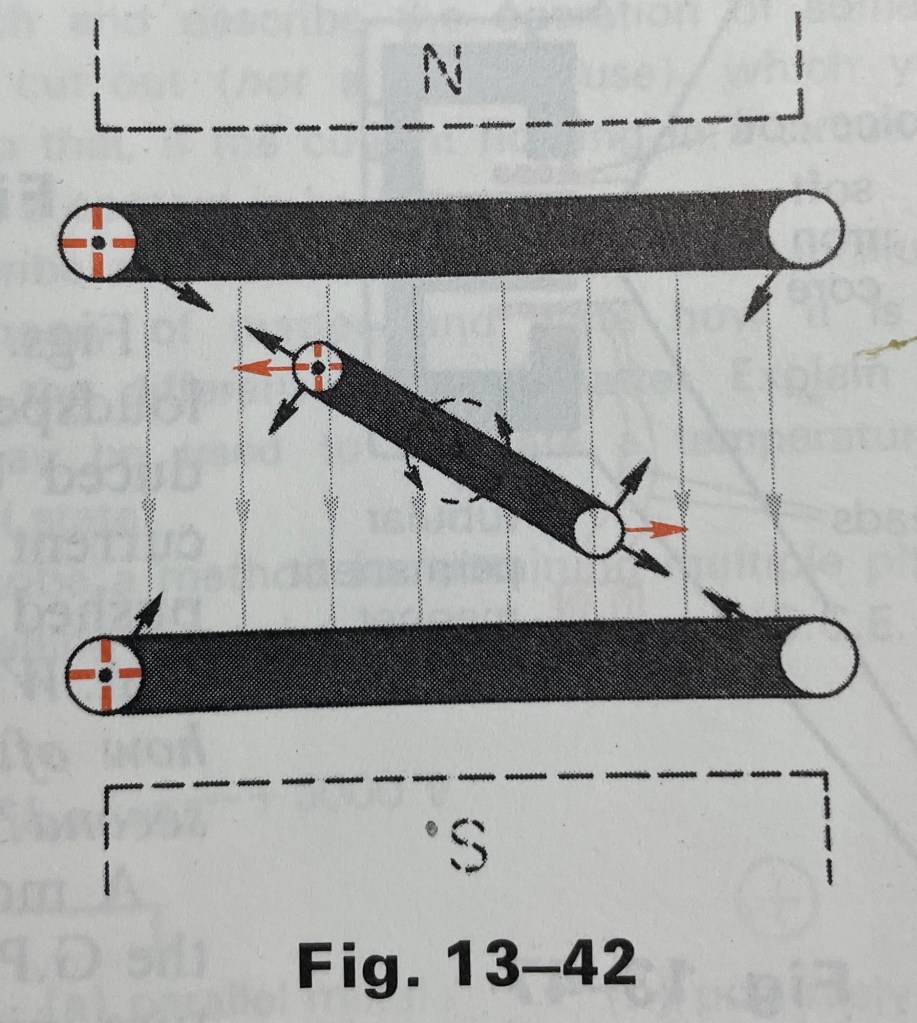

On p123-4 both black and red are used to simultaneously represent electron flow and conventional current as shown in the two figures below.

This perhaps illustrates that the simplicity of using electron flow in simple circuits starts to cause problems when one starts to get deeper into electromagnetism and move away from simple d.c. electric circuits with lamps and resistors.

Nuffield Teachers’ Guide II (1966)

At the same time as the Alternative syllabi were being developed in Scotland and Jim was writing his Physics is Fun books, at the UK level the Nuffield Ordinary-Level course was being developed, and Jim had a significant role in this, but mainly in the mechanics sections.

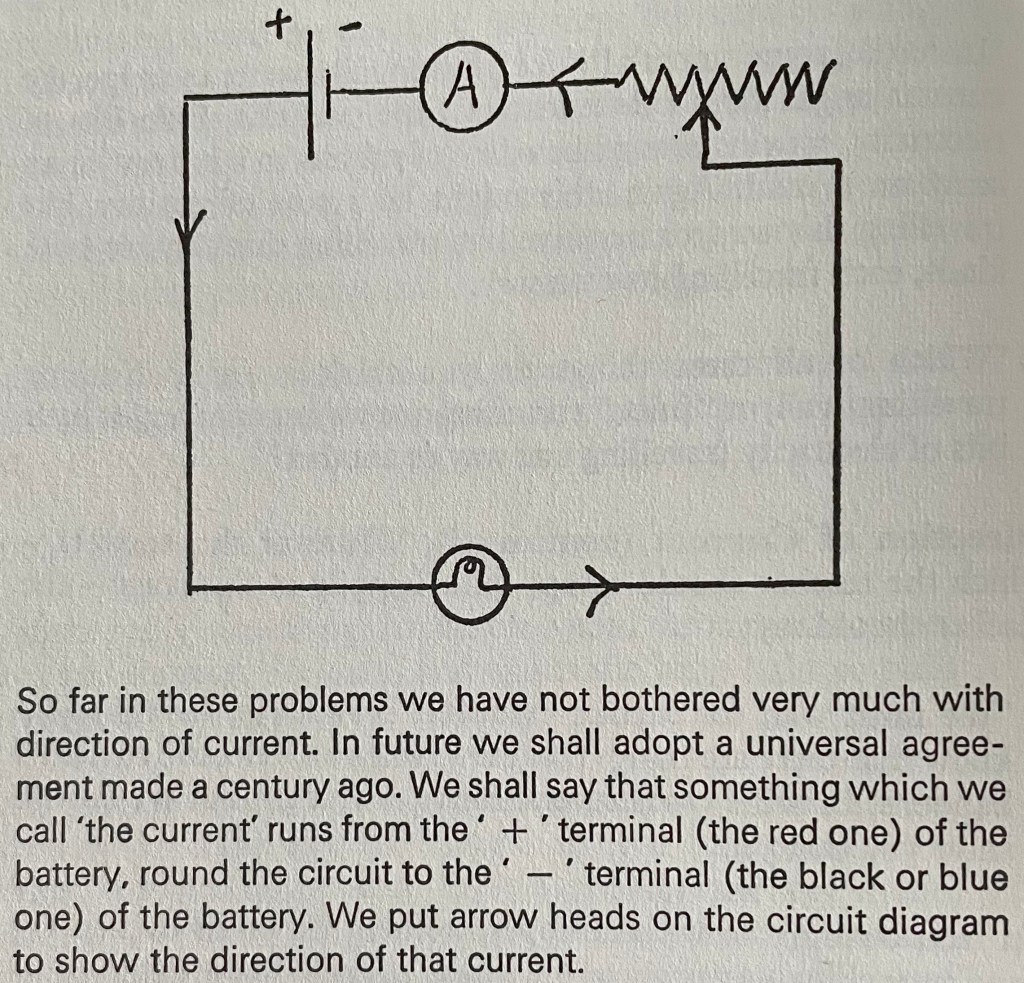

As part of a section dealing with the teaching of electricity the following appears on p40.

“So far….we have not bothered very much with the direction of current. In future we shall adopt a universal agreement made a century ago.”

All the Nuffield materials then go on to use conventional current, but at times mentioning how electrons move as appropriate. Whether or not there had been any debate during its development, it is clear that the decision was taken to stick with convention.

Science for the 70’s Books 1 and 2 (1971)

These books were written for the S1/2 curriculum of Curriculum Paper 7. On p111 in Unit 7 there is the statement “The electrons flow out along the wire connected to the negative terminal of the cell.” Otherwise the discussion is about relative brightness of lamps. However, in the Teachers’ Guide on p138 there is the Specific Objective:

“…the pupil should acquire:

2. the knowledge that current in a solid conductor is regarded as being a flow of electrons,”

In Science for the 70’s Book2 on p111, figure 15.15 and the surrounding text uses conventional current to determine the direction of the magnetic field around a current carrying conductor. However, from my experience, very few people ever had enough time to reach Unit 15 in the time available for science in S1/2.

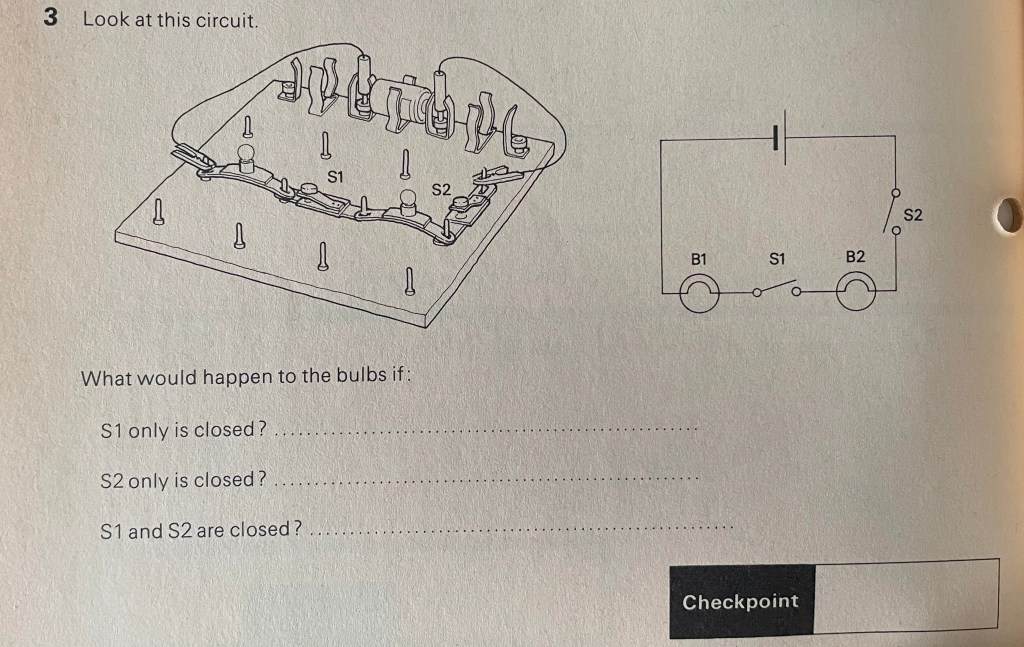

Scottish Integrated Science Worksheets and Teacher Guides (1977)

These were developed a working party set up by the Scottish Central Committee on Science responsible for Curriculum Paper 7 to allow a differentiated resource-based learning approach to teaching integrated science in S1/2. There is no specific directionality on diagrams etc but in the Teachers’ Guide Sections 1 to 8 on p131 the Section Objective:

“All pupils should acquire:

2. the knowledge that current is a flow of charge (electron)”

There is also a recommendation to use the symbols and practices in SCDS Memorandum 5 Symbols and Terminology in Physics (Second Edition) (1975). Although this lists the conventions for writing quantity symbols and units and circuit symbols there does not appear to be any recommendation on current direction.

The worksheets include many diagrams of the Worcester Circuit Boards developed as part of the Nuffield course mentioned above, but there is no direction of current on any of the diagrams.

Cackett, Kennedy and Steven’s Core Physics (1979)

This is arguably the most widely used textbook for O Grade, certainly for the last decade or more of the course.

On p184 it states “When we describe current in our circuits, we will be referring to the movement of electrons and this direction will be from negative to positive. In some textbooks the current is described as flowing from positive to negative. It is then often referred to as ‘conventional current’.” Arrows labelled I are then shown in subsequent figures in both circuits and magnetism sections.

Alistair Reid’s O-Grade Physics (1980)

In this book current arrows on circuit diagrams go from negative to positive and the right hand rule is used in the electromagnetism section. I cannot see any reference to conventional current or electron flow it appears to just assume current is negative to positive.

David Standley’s SCE O Grade Physics (1983)

This book explains both conventional current and electron flow on p163 with a helpful diagram showing a conventional current arrow on the circuit wire and an electron flow arrow separate from the wire and then avoids using direction arrows on figures. Conventional current is consistently used in the magnetism section (I might add that David taught in an independent school which also taught English syllabus courses which I am sure at least in part accounts for the difference in his approach to the other O Grade books above).

Conclusion

I think I have confirmed my hypothesis that there was no official planned attempt to redefine the international agreed definition of an electric current in any of the Scottish curriculum documents. Between the early 1960s and the early 1980s none of the syllabus or guidance documents state a requirement for one convention or another. I also know from my own experience in the 1990s and 2000s working for the SEB and then the SQA into which it morphed when it combined with SCOTVEC, that when Higher, CSYS, and Advanced Higher exams were written no specific mention of current direction was made and a great deal of care was taken to ensure questions could be answered by anyone using either electron flow or conventional current, including the avoidance of using potentially confusing arrows on diagrams.

However, it appears that following the lead taken in Jim Jardine’s Physics in Fun books, the emphasis was increasingly placed on using electron flow when explaining currents in metal conductors. Of course, in conductors other than metallic conductors, such as solutions, both positively and negatively charged particles can move. Electrons are only the dominant charge carriers in the, albeit very common, special case of metallic conductors but not in general. Thinking of a current only as a flow of electrons could cause misconceptions and misunderstandings for learners when subsequently applied more generally. Although Jim makes the distinction between the two approaches very clear in his early texts this is less so later. In subsequent texts published by other Scottish authors the idea that current is a flow of electrons becomes dominant. I suspect that by that time the subtle distinctions and teaching points that I am sure were discussed and considered to be very important by the committees involved during the development of the likes of the Alternative O Grade and Nuffield resources were being forgotten in the mists of time and the further one went from those involved in such discussions. I suspect there must also have been professional learning available when the Alternative Physics and Integrated Science courses were introduced that also promoted the use of electron flow. Hence, we arrived at a point when I entered teaching that Scottish physics teachers (and I include myself here) just accepted currents in school physics as electron flows because “that was the way it is” without necessarily appreciating the underlying philosophy – it might even be an example of “group think”, or what some might call “a cock-up rather than a conspiracy”.

As our learners live in an increasingly internationally connected digital world, they are likely to see webpages, animations, and more, all using conventional current. I think it is unfortunate that Scotland took the path it did with electron flow. Afterall, we cannot see any of the particles which may or may not be moving in a metallic conductor and when we are teaching simple d.c. circuits we are usually only ever interested in the magnitude of the current anyway, the direction is irrelevant, and to allow an argument about which direction it is in may just become a distraction from the main points we wish to teach (and I have not even broached the subject of a.c.). I also think that when it comes to teaching electronics and topics such as potential dividers and transistor switching circuits that sticking with all the well-designed conventions makes life much easier than any alternative. By the time we get to Advanced Higher and beyond, and the need to understand concepts such as electrical potential, it inevitable requires a switch back to describing everything in terms of positive charges as is consistent with conventional current. This causes an unnecessary switch for learners. Let us not make the understanding of physics any harder than it needs to be.

PS

I am still very envious of the quality of curriculum documents like Curriculum Paper 7 when you compare them with our current equivalents.

Leave a reply to Daniel Mallon Cancel reply