In the previous parts of this series of blogs, I explored the importance of good explanations in teaching and the potential benefits of good-quality textbooks and how good quality curriculum and teaching resources, including textbooks, might be developed. In this blog I will explore aspects of teacher professionalism and how this relates to these topics in the context of Scottish teachers.

Teacher professionalism

The use of scripted lessons, as discussed in the previous part in this series of blogs, cuts to the heart of professionalism and what it means for a teacher to be a professional. I would like to see teachers being able to act as transformative professionals critically engaging with research and policy much as the GTCS Professional Standards describe (GTCS, 2021a, 2021b). Teachers should be able to demonstrate teacher agency (Priestley et al., 2015) in a positive manner and take an activist, enquiring stance (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009; Sachs, 2003). On occasions, this could include using a teaching approach with which they might feel uncomfortable but for which there is strong evidence of its efficacy and of benefits for learners when using such an approach. I suspect that for many teachers in Scotland, especially given much of the culture and messaging around Curriculum for Excellence (CfE), the use of the Direct Instruction approach discussed in the last blog will fall into this category. However, in other walks of life, to not follow proven research-based approaches is seen as being unprofessional. For example, surgeons follow well-developed principles and protocols when in the operating theatre, as do airline pilots when readying their aircraft for take-off. They cannot just do something differently just because it is what feels right to them. Clearly the impact of a patient dying on the operating table or an aircraft falling out of the sky are much more dramatically obvious than something which perhaps might occur many years down the line, but it could be argued that the impact of poor teaching can be of significant detriment to the life chances of the young people involved. Working too autonomously in any profession is a not a good thing.

In other professions, agreed improved approaches were developed after significant research and experience, and often took some time to be accepted. It is a long time since surgeons considered it unnecessary to wash their hands because they were gentlemen and current practices have resulted after much research since the pioneering work of the likes of Joseph Lister and Florence Nightingale in the mid-1800s. Douglas Carnine, one of Zig Englemann’s collaborators, stated that education is an “immature profession” because it is characterised by expertise based on the subjective judgments of individuals rather than standardised procedures based on research findings and on a shared and commonly understood vocabulary (Carnine, 2000). I think it is important, that as a teaching profession, we develop a better shared vocabulary to describe teacher knowledge and teaching practices and as a result help prevent people speaking past each other. This is one of the reasons I am pleased to have been involved in work developing a knowledge framework for physics teacher and teacher educator knowledge (Farmer, 2024b; Institute of Physics, 2024) as this helps provide the profession with a common language to discuss practice and professional learning. The consultation responses gathered during its production indicated that a better agreed language for teacher would be appreciated by practitioners. The work of Doug Lemov grates for many in the UK because his language and tone comes across in a somewhat brash American way compared to the more reserved approach more common in the UK, however, his books do help provide a common language, including terminology for many everyday teaching practices which is often missing elsewhere (Lemov, 2021).

A more mature teaching profession should also be more actively engaged with and in educational research. Research can also take several forms and could and should involve that done by academics on school teaching as well as that by teachers themselves. This research should include randomised controlled trials, the analysis of national and international data sets, comparison studies similar in format to Project Follow Through described in my previous blog, as well as action research and practitioner enquiry conducted in the working context of the teachers involved. Enquiry-as-stance (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009) should be the norm for teachers. There also needs to be good opportunities for teachers and researchers to share their finding and break down the barriers that can exist between the educational research community and practising teachers. It will all help build up a common shared language for teaching.

My recent research has shown that enquiry-as-stance has not become the norm in Scotland, certainly not in its secondary schools, despite the national policies promoting it (Education Scotland, 2019; GTCS, 2021a, 2021b).

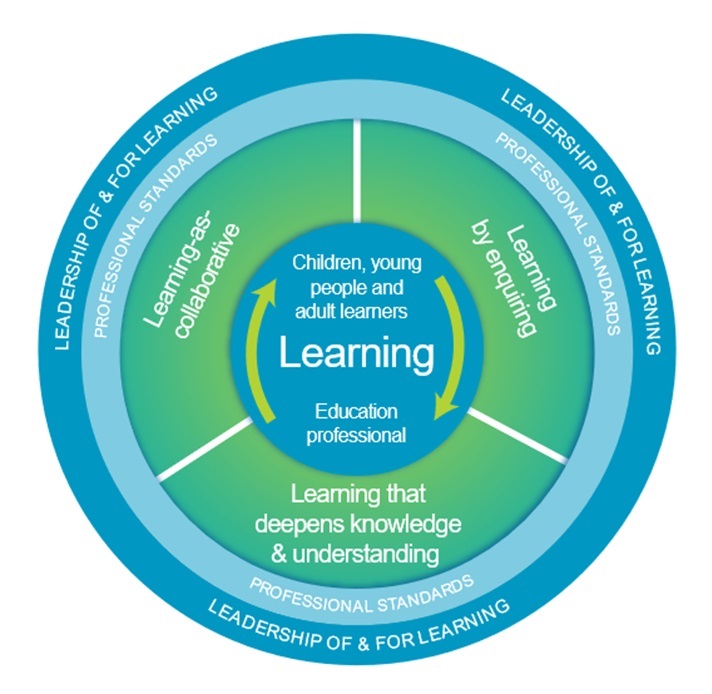

Figure: The National Model of Professional Learning in Scotland

That Scottish teachers are not more engaged with research and in collaborative professional enquiry is at least in part because teachers are time-poor thanks to a high class-contact commitment (OECD, 2021). The collegiate time which is available is used poorly and not prioritised for professional learning or enquiry (Farmer, 2024a). In general, time and funding for educational research are in short supply. Funding for teachers to complete Masters level qualifications has been directed at preparation for school leadership rather than for those wishing to focus on improving teaching and learning, and has been cut in recent years. I also think the culture in many educational organisations and establishments does not adequately value the benefits that either a more enquiring approach, or a more subject-specific approach, would bring. Inevitably a critical, enquiring approach will result in the status quo being challenged at times by teachers. A culture of compliance, an element of groupthink, and the dead hand of bureaucracy acts to stifle such challenge too frequently in Scottish education (Bhattacharya, 2021; Humes, 2021). Too often teachers are left only with opportunities to display agency through acts of resistance rather than through more positive forms.

Certainly, in my own field of physics and science education, much of the policy guidance and support provided to Scottish teachers since the introduction of CfE has not been well evidenced by research, and references to independent research are a rarity in many Scottish policy documents. For example, I wrote about the lack of emphasis placed on knowledge in CfE in a previous blog. I know I was not alone amongst science educators in being sceptical about the emphasis placed on a skills-based approach in CfE, not least in my case because I had already lived through the period that resources and methodologies based on developing science processes rather than specific knowledge were introduced in lower secondary by many schools in the late 1980s. These gave generally poor results leading to a fairly rapid abandonment of the approach in the 1990s. This was certainly the case in both schools I worked in during this period. This process science approach was also at the opposite end of the spectrum to Direct Instruction and an example of what Kirschner, Sweller and Clark have described as minimally guided instruction (Kirschner et al., 2006). Too often when such approaches are used, pupils are left too much to their own devices to find out things for themselves resulting in inefficient learning at best, and frustration for some which can potentially lead to behaviour problems.

Some argue that learners finding things out for themselves leads to more robust learning but there is little or no evidence of this being the case (Klahr & Nigam, 2004). I think the vast array of explainer videos one can now find on YouTube where an expert in something demonstrates and explains how a novice can learn about or do something shows the power of a good teacher explicitly showing a learner how to go about something. As well as modelling the task, good interactive explicit teaching also includes activities such as checking for understanding, providing further support where necessary, opportunities for repetition and practice, and a gradual removal of scaffolds as the novice learner develops expertise in the topic and can move on to more open-ended tasks. This is summarised well in the principles set out by Rosenshine (2012) and Dunlosky (2013). Teacher-led rather than student-led approaches are often mischaracterised as lecturing with students sitting passively in rows, but good teacher-led instruction ought to be highly interactive resulting in a great deal of cognitive activity on the part of the learners. Direct Instruction is a very good example of this. I think an effective critically enquiring, and professional, teacher should be able to draw on and engage with research literature on effective pedagogies to help improve their classroom curriculum and their pedagogical decision-making and to not feel constrained by an overly compliant education system promoting particular approaches.

Engaging with educational research

Time-poor teachers do not have much time to engage with educational research, do not always have access to it, and there is a vast range of research of variable quality and usefulness. There is a need for mediators between the research community and the teaching community. This can include teacher educators who have time to access and digest relevant research into forms more useful to busy teachers. I am pleased that in the field of physics that the Institute of Physics has summarised a huge array of physics education research into pupil misconceptions and made this available on their resources website (Institute of Physics, n.d.). This is an important step in making research available to teachers in a readily digestible form.

Teaching is a hugely complex task. Lee Shulman, who invented the term pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), when comparing the practising of medicine with teaching said:

“The only time a physician could possibly encounter a situation of comparable complexity [to teaching a class] would be in the emergency room of a hospital during or after a natural disaster.” (Shulman, 2004, p258)

Due to this complexity, and the ethics surrounding work with young people, many areas of education do not lend themselves to randomised controlled trials in the same way as medicine, but nevertheless it is incumbent on teachers, as critical enquiring professionals, to engage with the research literature and be open to change even when the findings of the research, including from a teacher’s own practitioner enquiries, make for uncomfortable reading and challenges strongly held views. However, if teachers are to address the issues of crafting good explanations, have an effective voice in shaping the institutional curriculum, collaboratively develop improved teaching resources, and make sound classroom curriculum choices, it is essential that teachers have improved access to good quality educational research and research briefings as well as opportunities to engage in collaborative professional enquiry and other forms of research themselves. By doing so teachers will be genuinely empowered to demonstrate teacher agency and transformative professionalism. For this to be the case, time must be freed up for teachers by removing some of the system expectations for them to engage in activities, mostly driven by an external accountability and scrutiny agenda, which do not support improvement in the instructional core in classrooms but drive performativity instead. It is not reasonable or possible to expect teachers to engage in such professional activities on top of an already overcrowded workload.

In the final part of this series of blogs, I will turn to thinking about how curriculum reform in Scotland could be taken forward to ensure it has a beneficial impact on the learning of our country’s young people.

References

Bhattacharya, A. (2021). Encouraging innovation and experimentation in Scottish schools. https://www.smf.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Innovation-and-experimentation-in-Scottish-schools-March-2021.pdf

Carnine, D. (2000). Why Education Experts Resist Effective Practices. https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/research/why-education-experts-resist-effective-practices-and-what-it-would-take-make

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (2009). Teacher Researcher as Stance. In S. Noffke & B. Somekh (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Educational Action Research (pp. 39–49). Sage.

Dunlosky, J. (2013). Strengthening the Student Toolbox: Study strategies to boost learning. American Educator, Fall, 12–21. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1021069.pdf

Education Scotland. (2019). National model of professional learning – detailed poster. https://education.gov.scot/professional-learning/national-approach-to-professional-learning/the-national-model-of-professional-learning/

Farmer, S. (2024a). The alignment of policy and practice for the career-long professional learning of teachers in Scotland [University of Strathclyde]. https://stax.strath.ac.uk/concern/theses/w66344189

Farmer, S. (2024b). A Knowledge Framework for Teachers of Physics and Physics Teacher Educators: The Genesis of a Knowledge Framework Based on the Knowledge Quartet. Education Sciences, 14(7), 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/EDUCSCI14070687

GTCS. (2021a). The Standard for Career-Long Professional Learning: An Aspirational Professional Standard for Scotland’s Teachers. https://www.gtcs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/standard-for-career-long-professional-learning.pdf

GTCS. (2021b). The Standard for Full Registration: Mandatory Requirements for Registration with the General Teaching Council for Scotland. https://www.gtcs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/standard-for-full-registration.pdf

Humes, W. (2021). The ‘Iron Cage’ of Educational Bureaucracy. British Journal of Educational Studies, 70(2), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2021.1899129

Institute of Physics. (n.d.). Misconceptions | IOPSpark. Retrieved 2 August 2024, from https://spark.iop.org/misconceptions

Institute of Physics (2024). Subject knowledge framework for teaching physics | IOPSpark. Retrieved 2 August 2024, from https://spark.iop.org/framework

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/27699659_Why_Minimal_Guidance

_During_Instruction_Does_Not_Work_An_Analysis_of_the_Failure_of_Construc

tivist_Discovery_Problem-Based_Experiential_and_Inquiry-Based_Teaching

Klahr, D., & Nigam, M. (2004). The Equivalence of Learning Paths in Early Science Instruction Effects of Direct Instruction and Discovery Learning. Psychological Science, 15(10), 661–667. http://lexiconic.net/pedagogy/KlahrNigam.PsychSci.pdf

Lemov, D. (2021). Teach Like a Champion 3.0: 63 techniques that put students on the path to college. Jossey-Bass.

OECD. (2021). Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence: Into the Future, Implementing Education Policies. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2021/06/scotland-s-curriculum-for-excellence_9de88365.html

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher Agency. Bloomsbury.

Rosenshine, B. (2012). Principles of Instruction Research-Based Strategies That All Teachers Should Know. American Educator, Spring, 12–19, 39. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ971753.pdf

Sachs, J. (2003). The Activist Teaching Profession. Open University Press.

Shulman, L. S. (2004). The wisdom of practice : essays on teaching, learning, and learning to teach. Jossey-Bass.

Leave a comment