The recent death of Tim Brighouse and the many tributes to him on Twitter have helped me crystalise some of my thoughts on improving the quality of teaching and with it the performance of the education system as a whole. This is essentially at the core of my PhD research and much of my professional activities stretching back many years. It was clearly central to Tim’s life’s work and his successes leading large education authorities but still knowing and communicating directly with teachers on a personal level, and fighting the corner of classroom teachers more broadly, have been well documented in recent days. One post on Twitter particularly stood out for me. It was by David Weston, founder and CEO of the Teacher Development Trust, and linked to a short video of Tim speaking at one of their early conferences ten years ago. Tim Brighouse – How to raise the quality of teaching https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gbGQd0QwbRo (Teacher Development Trust, 2013).

In the video, Tim paraphrases research findings of Judith Warren Little (1982) which very much resonate with my own views on the professional learning which is most likely to improve the quality of teaching and therefore the performance of the education system. It also led me to consider how Little’s study complements the findings of two other large studies from the United States which I have referenced frequently recently in talks and presentations and in my PhD thesis. I am now firmly of the view that the education system can be best improved through a relentless and consistent focus on professional learning aimed at improving teaching in classrooms. This professional learning therefore needs to be set significantly in the context of each individual teacher and relevant to the day-in-day-out work of the teacher and therefore to have a substantial subject-specific component (Cordingley, 2018; Institute of Physics, 2020; Leonardi et al., 2022). It also needs to have a significant school-based element but with input and challenge from appropriate knowledgeable others.

So, what did Tim Brighouse and Judith Warren Little say?

It can be summarised by four statements. The quality of teaching can be improved by:

- Teachers talking to each other about teaching.

- Teachers observing other teachers teaching (not just being observed).

- Teachers planning, organising and evaluating their work together.

- Teachers teaching each other.

I am sure many teachers who may be reading this are having an internal verbalising ‘no shit Sherlock’ moment but, given that Little came to this conclusion two years before I entered teaching, it is my experience that such a focus has been largely absent from the school and system improvement initiatives I have experienced or been aware of in the forty years since. Indeed, as has been confirmed by the data I have gathered from both my recent MSc research (Farmer & Childs, 2022) and that for my PhD, this has likely been the case for the majority of secondary physics teachers across the north of Scotland, and I have no reason to expect this to be any different for teachers of other subjects across Scotland. There have been some well documented exceptions (Berwickshire High School, 2023; Eyemouth High School, 2019; Gilchrist, 2018) but despite the policy drive towards the greater use of practitioner enquiry (Education Scotland, 2019; GTCS, 2021) many schools do not appear to prioritise in-service days, collegiate time, or career-long professional learning time on improving classroom pedagogy or subject-specific professional learning compared to whole-school administration and accountability activities, often driven by the fear of inspections and a continual focus on How Good Is Our School? (Education Scotland, 2015). This makes me think of the aphorism about measuring a pig not being the way to fatten it.

Little identified the four significant collegiate interactions listed above thanks to a yearlong ethnographic study in six schools, three elementaries and three secondaries. This included interviews and observations involving 105 teachers and 14 school administrators not only when teaching in classrooms but when interacting during in-service meetings, staffrooms, corridors and elsewhere. The six schools were chosen so that one of each of the elementary schools and secondary schools were seen as successful and with a high staff involvement in professional learning, one as successful but with low staff involvement in professional learning, and one as less than successful but with high involvement of staff in professional learning activities. From the large range of staff interactions observed and described, Little identified the four types of interactions listed above as those crucial for successful schools (Little, 1982, p331).

The findings of Little’s extensive study made me consider a comparison with Bryk et al.’s (2010) large study of school and system improvement in Chicago in the 1990s. The prologue in their book contrasts the progress, or lack of it, made by two schools in very similar areas of a city not without significant challenges and deprivation. Their findings have much in common with Little’s analysis of the successful and unsuccessful schools. Bryk et al.’s detailed analysis of the progress made in schools across the city was afforded by what was in effect a large multi-year experiment in school improvement following the Chicago School Reform Act of 1988 and allowed for the identification of factors most influential on school improvement.

Bryk et al. identified five essential supports. First, and probably the most fundamental is the importance of school leadership with a consistent focus on building agency for change across the school community. This leadership requires to be focussed on supporting the other four essential supports. The second essential support is the building of stronger school to parent and community ties and the third essential support is the building of staff professional capacity through an ethos of supporting staff professional learning and continual improvement in classroom practices. The fourth essential support is that of nurturing a student-centred learning environment where students feel safe but challenged and supported to engage and succeed. The final essential support is that of cultivating a consistent school-wide approach to teaching and learning through clear curriculum and pedagogical guidance, something championed in Scotland by Bruce Robertson, Headteacher at Berwickshire High School, in recent years (Robertson, 2020, 2021a, 2021b). There is much in Bryk et al.’s third, fourth and fifth essential supports that can be delivered through a consistent application of Little’s four collegiate interactions, but Bryk et al. remind us that no school is an island and good community relationships are also important for success and all of these supports are unlikely to lead to impact without effective leadership. There is also much in Bryk et al.’s essential supports that will resonate with Scottish teachers and the current issues prominent in the discourse around educational reform in Scotland, including the need to address pupil behavioural issues (Scottish Centre for Social Research, 2023), for clearer curriculum guidance (Campbell & Harris, 2023; OECD, 2021) and the use of improved, research and evidence informed pedagogies (Scottish Government, 2023a).

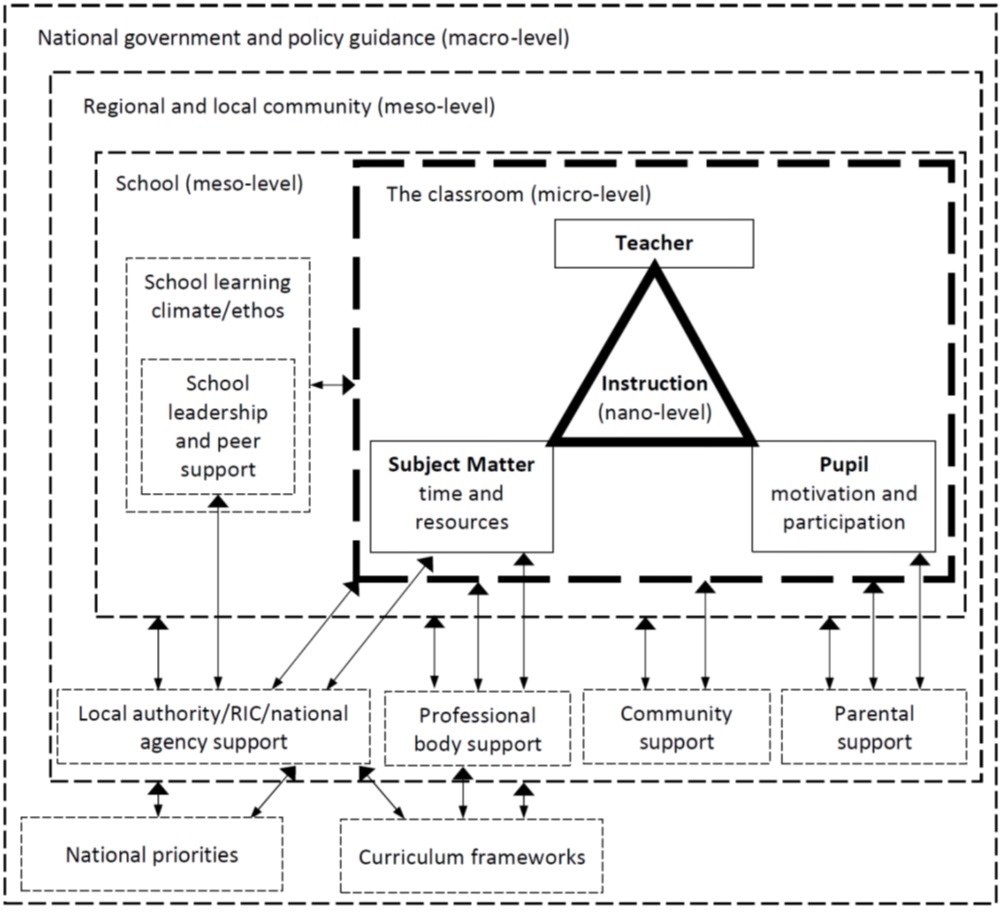

Through their analysis and conclusions, Bryk et al. always make it clear that the purpose of any reform is to improve the instructional, or pedagogical, core consisting of the interactions between the teacher, their pupils, and the subject matter they are teaching. Figure 1 illustrates how the instructional core, or nano-level of the education system, sits within and is influenced by the wider education system. A very similar instructional triangle, shown with professional learning influences on it, is referred to by Little in some of her later work (Little, 2006, p6).

Figure 1: A model showing the influences on the instructional core in the micro-level of the education system, adapted from Bryk et al. (2010, pp 48-51)

The third large study from the United States is Cobb et al.’s (2018) eight year study of the implementation of professional learning to improve the teaching of mathematics in four large urban school districts involving many hundreds of teachers and hundreds of thousands of pupils. Their conclusions were that successful curriculum development and improvement programmes had three essential components:

- Teacher professional learning:

- Conferences and stimulus events giving access to knowledgeable others,

- Instructional coaching by subject pedagogical experts,

- In-school collaborative time facilitated by subject pedagogical experts,

- Teacher networks to facilitate between-school collaboration.

- Instructional materials and assessments developed by groups of curriculum and pedagogical experts.

- Supplementary supports for currently struggling students.

This sort of professional learning provision encompasses the sorts of supports identified by teachers interviewed during my PhD research when asked to described what they considered to be their ideal professional learning provision, and is consistent with what has been said by Scottish teachers in the reports of Muir (2022) and Campbell and Harris (2023, pp51-2).

Cobb et al.’s essential components of successful professional learning are also consistent with Little’s four collegiate interactions and provide a structure to facilitate impactful professional learning. Apart from some of the likely inputs at conferences being from ‘external’ experts, the majority of the professional learning involves teachers talking about teaching with other teachers, but importantly often facilitated by expert colleagues taking a coaching or facilitation role to ensure an effective structure to the professional learning which challenges the status quo and avoids the danger of either the “sharing of ignorance” (Guskey 1999, p12) or “contrived collegiality” (Hargreaves & Dawe, 1990). The role of subject pedagogical experts trained to support the professional learning of other adults through instructional coaching, during collegiate time in schools, and in between-school networks is key to ensuring transformative subject-specific professional learning. The middle of Cobb et al.’s three essential components is having high quality instructional materials developed by those with good curriculum development and pedagogical expertise. Having well-constructed instructional materials for teachers to use and adapt as appropriate in their local context has been sadly lacking in Scotland since the introduction of Curriculum for Excellence resulting in an unnecessary increase in teacher workload. As well as clear curriculum guidelines, teachers deserve access to well-written resources rather than all teachers being expected to be excellent curriculum and resource developers as well as pedagogical experts in the classroom (Campbell & Harris, 2023, p60). I find the third of Cobb et al.’s essential components particularly interesting as it emphasises the importance of good early intervention for struggling pupils with the aim of getting them back on track and preventing the development of an attainment gap which will become increasingly difficult to close as time passes.

The findings of Little, Bryk et al. and Cobb et al., based on the observation of the practices of large numbers of teachers and schools, provide robust evidence that when teachers do talk to each other about teaching, plan and evaluate together, and participate in structured professional learning facilitated by subject and pedagogical experts that the quality of teaching improves giving better pupil attainment and system performance. However, this is inevitably a greater challenge in the many schools in the remote and rural (Scottish Government, 2022) areas in the local authorities in the Northern Alliance Regional Improvement Collaborative than it is in densely populated urban areas in the United States. The data I have gathered for my PhD shows that the professional learning most valued and desired by physics teachers in the north of Scotland does match well with that identified in the three American studies. For example, when asked to identify the ideal professional learning provision, one of the teacher participants provided a concise list:

- Good relationships with school colleagues and mechanisms in place to allow activities such as learning visits and peer observation.

- Regular meetings and good networking with other subject colleagues in the local authority or schools nearby to discuss teaching and learning of the subject.

- Opportunity to attend at least one national or international conference per year giving the opportunity to meet with people from different backgrounds and with different experiences.

- Encouragement and financial support to undertake additional qualifications such as Masters courses.

- The maintenance of an online professional learning offer, beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing teachers to dip into professional learning at times convenient to them.

This list has much in common with those above but also reflects the changes brought about by improved technology for online working and a change in attitude towards it use thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic. The inclusion of attending national or international conferences should also not be underestimated. These provide access to high profile speakers and other knowledgeable others not possible in local school settings. They also provide informal networking and professional learning opportunities around the more formal sessions. The outcomes of these always have a serendipitous element and are difficult to predict. Such informal professional learning opportunities are often undervalued (Eraut, 2012; Evans, 2019; Netolicky, 2019), particularly by decision-makers looking for predictable outcomes, but the COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated that the ‘side conversations’ during such events can lead to innovation in a manner difficult to replicate in a Teams or Zoom meeting.

In relatively small secondary schools, often some distance from their nearest neighbours, there are many staff who are the only person teaching a particular subject. How do such teachers talk to other teachers about the details of teaching their subject, or observe others teaching that subject? This is an issue in which I have been interested in for some time and have worked, mainly through the Institute of Physics (IOP), to support communication between Scottish physics teachers, particularly relatively isolated teachers in remote and rural areas. This is no doubt influenced by being the only physics teacher in a small secondary school in rural Aberdeenshire for a period fairly early in my career. I was one of the IOP team that set up the SPUTNIK (name evolved from Scottish Physics Teachers News and Comment) email forum at the start of 2004. It has proved invaluable as a means of peer support over the last twenty years and in enhancing the sense of community amongst Scottish physics teachers. It is still going strong even through a change of IT platform which is taking place this month. More than 600 Scottish physics teachers have actively engaged with SPUTNIK in the last few weeks as it transfers to NEW SPUTNIK on Google Groups. Many of the teacher participants in my PhD study made very positive comments about SPUTNIK such as:

“Since I’ve been teaching in Scotland SPUTNIK has been probably my go to thing especially early on in my career, ‘How do I do this?’ or ‘Any ideas for this?’, and then just reading other peoples’ ideas, I found very valuable.”

“SPUTNIK … was an absolute revelation, it really was good, just to have, well, to discover that there were so many physics teachers out there to learn from.”

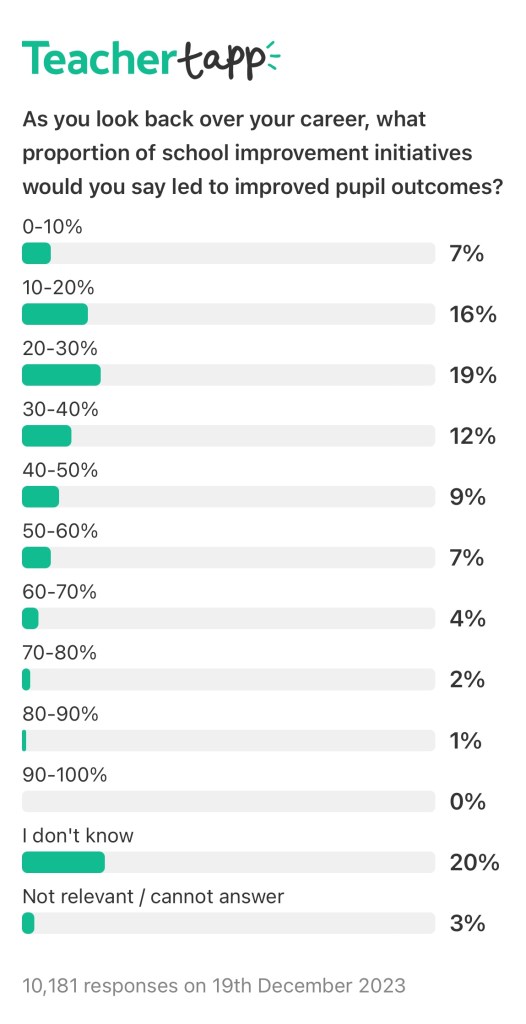

However, an email forum has its limitations and I have also been interested in developing, maintaining and growing between-school networks to facilitate relatively isolated teachers talk about physics teaching with each other (Farmer, 2018; Farmer & Childs, 2022). It is unfortunate that during this work, essentially for a third sector professional body sitting somewhat outside the ‘system’, I and many of the teachers who wished to participate and benefit rarely met with significant support for doing so from their school and local authority leadership. More typical responses have been indifference or even hostility towards such activities which promote teachers talking to each other about subject-specific teaching and learning. It was this resistance in the face of what is found in the research literature, much national policy guidance, and the desires of the teachers involved that led me to embark on a PhD to investigate why there seemed to be such a misalignment between professional learning policy and practice. Almost all the teacher participants in my study have very negative opinions about most whole-school professional learning activities and consider in-service days and collegiate time to be used poorly. This appears to be a view shared by many teachers on TeacherTapp, most likely mostly from England. Just yesterday, the TeacherTapp results showed that around 55% of the almost 8000 teachers who provided a view considered that fewer than 30% of school improvement initiatives had led to improved pupil outcomes, see figure 2.

Figure 2: TeacherTapp – What proportion of whole-school improvement initiatives led to improved pupil outcomes? – 19 December 2023

From my PhD data, the successful whole-school improvement initiatives which enjoy good buy-in from teachers appear to be very much focused on improving pedagogy and largely down to the expertise of particular individuals in key school middle and senior leadership positions. These activities also appear to tend to draw on expertise and resources largely from beyond the normal provision from schools, local authorities or national agencies. It appears the leadership and culture in some schools can promote positive teacher agency but that this may be relatively rare. The views of most teachers towards whole-school professional learning or improvement activities seem to have changed little since the introduction of in-service days and collegiate time in the form of Planned Activity Time (PAT) as part of the agreement following the Main Report (Main, 1986). In their review of the introduction of PAT, Inglis et al. (1993) wrote that “the 10 hours devoted to whole-school activities in secondary schools seemed to most staff a complete waste of time” but “there was almost unanimous agreement that PAT activities at departmental level were valuable” (p362).

It is my experience that it is the pretty unanimous view of teachers that they would like to talk about teaching with other teachers who teach the same subject(s) in similar contexts to themselves, and take part in the rest of the collegiate interactions identified as most beneficial for school improvement by Judith Warren Little and reiterated by Tim Brighouse. Teachers see this as the best means to improve the quality of their teaching and the outcomes of their pupils. It is unfortunate that many of the structures and much of the time and effort of those in the meso-level of Scottish education appear to have different priorities, often driven by an accountability or scrutiny agenda rather than one of genuine support and improvement.

It is important at this crucial time of educational reform in Scotland that decisions are made which enable existing and new agencies to facilitate and support effective subject-specific professional learning for teachers and enable the communication and networking required. This will require time, and the promised additional 90 minutes of non-contact time (Scottish National Party, 2021) is badly needed. However, this time must be used wisely. This will require staff with the knowledge and skills to lead professional learning, to engage in instructional coaching, and to facilitate between-school subject networks, professional learning communities, lesson study, or cycles of practitioner enquiry. Perhaps roles for lead teachers (SNCT, 2021) with the remit of facilitating truly transformative subject-specific professional learning. No matter how it is delivered, the key to improving the education system is a structured, purposeful focus on improving instruction in classroom by facilitating teachers talking, observing, planning, evaluating, and teaching together.

The recent Scottish Government consultation (Scottish Government, 2023b) asked how the views of teaching professionals can be best taken into account by the new qualification body for Scotland. This needs to include the views of teachers in places like Kirkwall or Kirkcudbright just as much as those in places like Kirkliston or Kirkintilloch. I think it is important if we are going to see the culture change I consider necessary that the voices of teachers are heard and acted upon not only in any new qualifications or inspection bodies but throughout the organisations tasked with the delivery of education in Scotland but also that many leaders in these organisations be ‘more Tim Brighouse’.

References

Berwickshire High School. (2023). Berwickshire High School – Inspection. https://www.berwickshirehighschool.co.uk/page/?title=Inspection&pid=111

Bryk, A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., & Easton, J. Q. (2010). Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago. University of Chicago Press.

Campbell, C., & Harris, A. (2023). All Learners in Scotland Matter: The National Discussion on Education Final Report.

Cobb, P., Jackson, K., Henrick, E., & Smith, T. M. (2018). Systems for Instructional Improvement: Creating Coherence from the Classroom to the District Office. Harvard Education Press.

Cordingley, P. (2018). We need to talk about subjects: findings from a review of subject-specific professional development and learning for teachers (pp. 1–18). CUREE.

Education Scotland. (2015). How good is our school? (4th ed.). Education Scotland.

Education Scotland. (2019). National model of professional learning – detailed poster.

Eraut, M. (2012). Developing a broader approach to professional learning. In A. McKee & M. Eraut (Eds.), Learning Trajectories, Innovation and Indentity for Professional Development (pp. 21–45). Springer.

Evans, L. (2019). Implicit and informal professional development: what it ‘looks like’, how it occurs, and why we need to research it. Professional Development in Education, 45(1), 3–16.

Eyemouth High School. (2019). Read our GTCS Excellence in Professional Learning Award report. https://www.eyemouthhigh.org.uk/news/?pid=0&nid=1&storyid=46

Farmer, S. (2018). Networked professional learning of physics teachers in a remote area in Scotland. University of Oxford.

Farmer, S., & Childs, A. (2022). Science teachers in northern Scotland: their perceptions of opportunities for effective professional learning. Teacher Development, 26(1), 55–74.

Gilchrist, G. (2018). Practitioner Enquiry: Professional Development with Impact for Teachers, Schools and Systems. Routledge.

GTCS. (2021). The Standard for Career-Long Professional Learning: An Aspirational Professional Standard for Scotland’s Teachers.

Guskey, T. R. (1999). Apply time with wisdom. Journal of Staff Development, 20(2), 10–15.

Hargreaves, A., & Dawe, R. (1990). Paths of Professional Development: Contrived Collegiality, Collaborative Culture, and the case of Peer Coaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 6(3), 227–241.

Inglis, B., Ballantine, L., Hepburn, M., & Riddell, S. (1993). Planned activity time: A Scottish experiment in making school and personal professional development a compulsory part of a teacher’s contract of employment. Research Papers in Education, 8(3), 355–368.

Institute of Physics. (2020). Subjects Matter: A report from the Institute of Physics.

Leonardi, S., Lamb, H., Spong, S., Milner, C., & Merrett, D. (2022). Meeting the challenge of providing high quality continuing professional development for teachers: The Wellcome CPD Challenge: Evaluation Final Report.

Little, J. W. (1982). Norms of Collegiality and Experimentation: Workplace Conditions of School Success. American Educational Research Journal, 19(3), 325–340.

Little, J. W. (2006). Professional Community and Professional Development in the Learning-Centred School. National Education Association.

Main, P. (1986). Report into the pay and conditions of service of school teachers in Scotland.

Muir, K. (2022). Putting Learners at the Centre: Towards a Future Vision for Scottish Education.

Netolicky, D. M. (2019). Transformational Professional Learning: Making a Difference in Schools. Routledge.

OECD. (2021). Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence: Into the Future, Implementing Education Policies.

Robertson, B. (2020). The Teaching Delusion: Why teaching in our schools isn’t good enough (and how we can make it better). John Catt.

Robertson, B. (2021a). The Teaching Delusion 2: Teaching strikes back. John Catt.

Robertson, B. (2021b). The Teaching Delusion 3: Power-up your pedagogy. John Catt.

Scottish Centre for Social Research. (2023). Behaviour in Scottish Schools 2023.

Scottish Government. (2022). Scottish Government Urban Rural Classification 2020. https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-government-urban-rural-classification-2020/

Scottish Government. (2023a). Centre of Teaching Excellence. https://www.gov.scot/news/centre-of-teaching-excellence/

Scottish Government. (2023b). Education Bill provisions: consultation.

Scottish National Party. (2021). Scotland’s Future: SNP Manifesto 2021.

SNCT. (2021). The SNCT Lead Teacher and Career Progression Working Group Report.

Teacher Development Trust. (2013). Tim Brighouse – How to raise the quality of teaching – YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gbGQd0QwbRo

Leave a comment