During my reading for my PhD exploring the professional learning of teachers in Scotland it became clear that it was necessary to explore what is understood about the words ‘professional’ and ‘learning’. This helped me identify some of the main issues I required to focus on during my research. Here I explore more fully than space allows in my PhD thesis, the concept of professionalism, particularly as it manifests itself in relation to the Scottish teaching profession.

1. The nature of a ‘profession’

The word ‘profession’, and its derivatives, is used in a wide range of contexts which makes a discussion of the nature of professionalism complex. The use of the word ‘professional’ can be used to just describe ‘a jobwell done’, such as when someone completes some DIY home decorating to a high standard of finish. In terms of describing people and occupations, its use can extend from describing someone who makes a living from a full-time occupation which might otherwise be seen as a hobby or leisure activity for the majority, such as a professional musician or professional sportsperson, to those that are seen to practise ‘traditional’ professions, such as medicine, law, or the clergy. In addition to the traditional professions there are a group of semi-professions, or more modern or aspiring professions, frequently occupations which have had a greater proportion of female workers such as librarianship or nursing, and to which many might assign teaching.

Writing over twenty years ago, Hargreaves (2000) described teaching, at least in most Anglophone countries, as having gone through three ages during the 20th Century, and being about to enter a fourth. He describes the first age as the pre-professional age, where teaching was seen more as a craft rather than a profession. This was followed by the autonomous professional age, where teachers had considerable autonomy within their contexts and communities and shared many features with the traditional or classical conceptions of professionalism. This was in turn followed by the collegial professional age, where due to the increased recognition of the complexities of teaching more heteronomous collaborative professional cultures developed. At the time of his writing, Hargreaves saw teaching at the cusp of entering a new fourth age, the postmodern professional age with teacher professionalism under tension between competing forces pulling the teaching profession in the direction of de-professionalisation, such as the increased central prescription of curriculum and increased monitoring and accountability procedures, and at the same time in the direction of a more advanced, transformative professionalism with a greater emphasis on teacher professional learning, forces he described in more detail a few years earlier (Hargreaves & Goodson, 1996, pp1-3). Hargreaves wrote in an international context, and how closely his characterisation of this fourth age will have matched reality during the subsequent two decades will have varied depending on national political contexts as well being influenced by global influences such as the international comparative studies of the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, n.d.). However, as will be discussed further below, in a Scottish context the concept of teacher professionalism has certainly been pulled in different directions by different policy decisions and their enactment much as in the postmodern age Hargreaves described.

The concepts of a profession and of professionalism are clearly dynamic ones, and therefore ones for which it is difficult to give a precise definition. Gewirtz et al. (2009, p3) avoid attempting to define the concepts but make the distinction between a ‘profession’ as an occupational category and ‘professional virtues’. It is these professional virtues that are at the root of professionalism, both in terms of a mode of social control and of occupational characteristics or behaviours.

Kolsaker (2008, p516) claims that professionalism is a challenging concept as it is under-researched, and the research that does exist is frequently criticised as ambiguous and lacking in a solid theoretical basis. She goes on to say it is difficult to identify and define the constitution and characteristics of professionalism. Downie (1990, p147) suggests that a solution to this issue is to think of ‘family resemblances’ that describe professions rather than seek a list of necessary and sufficient conditions for professionalism which will inevitably throw up problems with borderline cases. Downie then goes on to list several characteristics:

- professions have a knowledge base, based on a broad education rather than on narrow training

- a service is provided through a relationship between the professional and clients requiring ethics and integrity which are authorised through an institution and legitimised through public esteem

- professions have an important social function as regulators in the interest of general utility and justice

- professions are seen to be independent to fulfil its various roles in society.

As a result, a profession will possess moral as well as legal legitimacy and its pronouncements will be listened to with respect; it will have legitimised authority.

In applying his analysis of professionalism to teaching, Downie highlights the need to distinguish the knowledge base of a teacher from that of a scholar. A central aspect of the knowledge base of a teacher is the communication of their knowledge to the ‘clients’, their pupils or students. This distinctive professional knowledge base includes what Shulman (1986) first referred to as pedagogical content knowledge, or the range of knowledges described by Rowland and colleagues (2005, 2013) in their Knowledge Quartet. Downie describes that to be educated a person must have wide cognitiveperspectives, the inclination to develop their knowledge and skills, and to develop them within a framework of values. In Scotland teachers are require to have a degree with sufficient content of the subject(s) they teach together with an initial teacher education (ITE) qualification and a requirement and entitlement for ongoing career-long professional learning. Values are prominent in the General Teaching Council for Scotland’s standards for registration as a teacher in Scotland (GTCS, 2021b) and include statements on: social justice; integrity; trust and respect, and professional commitment. It would appear that teaching in Scotland easily meets the first bullet point above.

In addressing the second bullet point (Downie, 1990) states:

“The fact that some people can learn without a teacher, or buy their own medicaments without medical advice, does not invalidate the claim that the professions, including teaching, provide their services through a special relationship.” (p158)

Even with developments in technology, the lockdowns of the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that the role of the teacher is central in promoting pupil learning.

Regarding the third bullet, to teach in Scotland it is necessary to be registered with the General Teaching Council for Scotland. It was set up in 1965 and has been independent of government since 2012 (GTCS, n.d.), although as Watson and Fox observe the GTCS has been “at pains to both align and distance itself from government” (2015, p136) casting doubt on how independent from government influence the GTCS truly is. Teaching in Scotland nevertheless is seen to have a self-regulating regulatory institution which helps legitimise teaching as a profession in the eyes of the public. In addressing the third point Downie states that everyone has a view on education, all having experienced many years of it during their own schooling, and therefore are likely to have had more direct experience of it than of the traditional professions such as medicine or law for example. However, he then goes on to point out that this does not mean that teachers cannot, or perhaps should not, speak with authority on educational matters, and indeed raises the issue that teachers ought not to allow that authority to be undermined just because others have views, often ill-informed views, on the matter. This does raise the question of how much of a voice, or influence, teachers have currently on educational matters in Scotland, especially as many employment contracts restrict this voice (Commission on School Reform, 2022).

In addressing the fourth bullet, Downie highlights that there can never be an independence from the public or political debate at any moment in history, and that remains as true for the teaching profession in Scotland today as it has done at any point in the past. However, the fact that the General Teaching Council for Scotland gained independence from government in 2012 means in terms of self-regulation and governance there is a sound basis for teaching in Scotland retaining a good degree of independence should teachers wish to exercise it. Using Downie’s ‘family resemblances’ as a means of analysis it would appear that teaching in Scotland meets his criteria for being considered a profession. However, the nature of professionalism itself can manifest itself in many forms and it is necessary to consider this in more detail.

2. The nature of ‘professionalism’

A professional occupation is traditionally seen as one which is based on:

- the use of skills based on theoretical knowledge

- education and training in those skills is certificated by examination

- a code of professional conduct oriented towards the ‘public good’

- a powerful professional organisation (Whitty, 2008, p28)

These four points are consistent with the ‘family resemblances’ identified by Downie. Teaching in Scotland can certainly claim to be consistent with the first three, although whether it is consistent the fourth is perhaps more debatable, and indeed may be part of the reason that this discussion is being had. It could be argued that successful traditional professions, such as medicine and law, have had strong professional organisations for a long time, but even powerful modern professionals such as surgeons can trace their origins back to a pre-professional age of the barber shop.

By analysis of the place of teaching and its political context in the UK, particularly in England, Whitty (2008) identified four modes, or conceptions, of professionalism:

- traditional – where teachers are trusted members of society

- managerial – where the state asserts expectations of teachers

- collaborative – which focusses on inter-profession collaboration

- democratic – where teachers are agents of change.

Kennedy, Barlow, and MacGregor (2012, p5) see these four conceptions not so much as discrete categories of professionalism but ways of explaining the existence of different manifestations of power. The way in which professionalism is conceptualised within the profession, by policymakers and through policy can therefore have a significant impact on the behaviour and efficacy of the profession itself and the enactment and effect of educational policy.

An important aspect of professionalism is the capacity to exercise discretionary judgements in situations of unavoidable uncertainty; reflection-in-action as described by Schön (1983). However, as can be seen from the analysis of Downie and Whitty, there are different conceptions of professionalism, each of which if promulgated and enacted, will result in different professional cultures which are largely dependent on the way power relationships are enacted. An important aspect of developing and enacting a democratic conception of professionalism, and thereby changing the culture within the teaching profession, is that teachers must identify themselves as ‘agents of change’ rather as ‘victims of change’ (Whitty, 2008, p45). This is consistent with Sachs’s (2003) ‘activist teacher’, where she introduces the concept of ‘activist teacher professionalism’ as a form of ‘transformative professionalism’. This very much overlaps with Whitty’s concepts of collaborative and democratic professionalism as it includes teachers not only being agents of change but also working collaboratively “not only with other teachers but also with others interested in education and improving student outcomes” (p15). Sachs contrasts transformative professionalism with ‘old teacher professionalism’ which similarly overlaps with Whitty’s concepts of traditional and managerial professionalism. Sachs states that the development of an activist teacher profession relies on teachers developing an activist identity, which itself can be traced back in origin to Dewey’s ideas around democracy in education (Dewey, 1916; Sachs, 2003, p130), where teachers believe they can effect meaningful change and construct their own self-narratives. Sachs acknowledges this is not straightforward to develop, nor is easily acquired in a climate where managerialism is strong (p134) and where cultures of compliance can dominate. Sachs states that achieving an activist teacher profession is premised on developing three concepts: trust; active trust, and generative politics, all necessary conditions for a politics of transformation to emerge. Trust has several functions in society, it contributes to cohesion and reduces complexity, but it involves an element of risk and uncertainty, can be slow to build, and may indeed be never completely attainable, and be lost very quickly. Active trust is built through effective collaboration and increasing the visibility and transparency in social relations. Generative politics is central to transformation as it encourages individuals and groups to make things happen rather than to allow things to be done to them.

In much the same way as Sachs’s transformative professionalism appears to be an amalgam of Whitty’s collaborative and democratic professionalisms, Hargreaves and O’Connor (2018) promote the term ‘collaborative professionalism’ to mean more than Whitty, and for it to also include many of the aspects of Whitty’s democratic professionalism. Hargreaves and O’Connor describe collaborative professionalism as going beyond teachers merely collaborating, both with each other and with others, but transforming teaching and learning through a form of professionalism based on ten tenets which they state distinguishes it from previous conceptions of professionalism. These tenets are: collective autonomy; collective efficacy; collective inquiry; collective responsibility; collective initiative; mutual dialogue; joint work; common meaning and purpose; collaborating with students, and big-picture thinking for all (Hargreaves & O’Connor, 2018, pp6-7). Whilst this list has much in common with list which could be created for other conceptions of professionalism, the emphasis is clearly placed on the professionalism not just of the individual but also of the group, whatever form that community of practice (Wenger, 1998) takes. Hargreaves, writing with Fullan (Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012) and drawing on the ideas of Bourdieu (1986), has also promoted the use of the concept of ‘professional capital’, itself composed of the three components ‘human capital’, ‘social capital’ and ‘decisional capital’, as describing the desirable outcome in which professional learning promoting transformative professionalism ought to result. They contrast this with a deficit oriented ‘business capital’ approach to professional learning consistent with a managerial conception of professionalism.

Boylan et al. (2023), in reviewing the literature in this area acknowledge there are many overlapping terms used for related constructs and classify activist, transformative, and democratic professionalism as ‘critical professionalism’ which they describe as including teachers not only being agents of change but also working collaboratively. They go on to relate critical professionalism to the characteristics of transformative professional learning which they identify as:

- purpose – for educational, social, and political transformation

- agency – to suppose activist professionalism

- sociality – collaborative partnerships

- knowledge – criticality about knowledge and knowledge production

However, they also identify that transformative professional learning displaying these characteristics can be enacted in different ways such as collaborative enquiry and practitioner research, or workshops led by experts and peers.

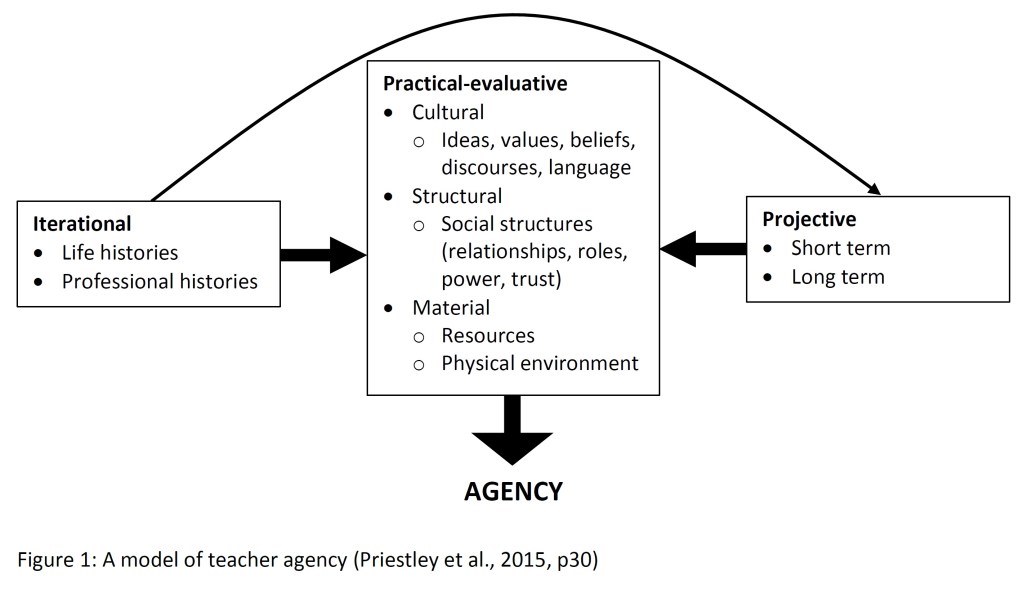

In many ways a more transformative form of professionalism strikes at the fundamental difference between teacher autonomy and teacher agency, terms that are nevertheless often conflated (Priestley et al., 2015, p141). Autonomy allows a high degree of self-direction and decision-making and an autonomous teacher can work with relatively little externally imposed accountability or control and is perhaps most strongly associated as a characteristic of traditional professionalism. Autonomy does not necessarily lead to professional behaviours and whilst it may be personally satisfying for the individual it is not likely to lead to a successful education system. Within an education system there requires to be an element of collegiate and collaborative working where individuals play a responsible part in that system, for example, to ensure coherent experiences for a child as they pass between different teachers as they progress through that system. In their seminal paper “What is agency?” Emirbayer and Mische (1998, p962) state “The concept of agency has become a source of increasing strain and confusion in social thought” and “the term agency has maintained an elusive, albeit resonant, vagueness”. Priestley, Biesta and Robinson (2015) build on the work of Emirbayer and Mische, particularly in terms of how agency relates to teachers and teaching, to better conceptualise ‘teacher agency’ and describe it as “not something that people can have or possess; it is rather to be understood as something that people do or achieve. It denotes a ‘quality’ of the engagement of actors with temporal-relational contexts-for-action, not a quality of the actors themselves.” (p22). They developed a model for conceptualising and theorizing their ecological approach to teacher agency which shows the contribution to, and interaction between, key dimensions of teacher agency, see figure 1.

Sachs (2003) states “responsibility and professionality go hand in hand” (p10) and also “it is no longer useful to place accountability and autonomy in opposition” (p9). A teacher may still be able to achieve agency within a system with externally defined policy that specifies goals and processes, but which allows the individual to make decisions and influence enaction within the broad policy framework. This of course includes teachers shaping the direction of their own professional learning.

3. Teacher professionalism in Scotland

For teachers in Scotland, perhaps the most readily available definition, or at least description, of professionalism can be obtained in the documentation of the General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS). Whilst such a definition may not be stated concisely in any one of its documents it has published a position paper on teacher professionalism and professional learning (GTCS, 2017). It is stated that teacher professionalism is “firmly rooted in or values, beliefs and dispositions” (p1) and goes on to describe, visually in a diagram, see figure 2, the key principles on which teacher professionalism in Scotland is built.

Collaborative professionalism is clearly an important aspect of the description and it also “locates teachers as key agents of educational change” (p3) making reference to the work of leading academics in the field of teacher professionalism and teacher agency (Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012; Priestley et al., 2015; Sachs, 2016). Tom Hamilton, former Director of Education, Registration and Professional Learning at the GTCS, describes there being a “GTCS model of the teacher” (Hamilton, 2018, p877) on which it has based its documents such as standards and guidelines. He lists a number of attributes and acknowledges the debt that ought to be paid to the work of Sachs, Hargreaves, and others such as Stenhouse, Fullan, Darling-Hammond and Cochran-Smith in informing this conception of a model teacher, although they are not generally referenced in GTCS documents such as its professional standards, as is also often the case in many documents from the Scottish Government, and its agencies such as Education Scotland, where references to academic research are a scarcity. The general lack of references could be argued as a means of controlling the narrative of the documents (Scott, 2000, p20). According to Humes et al. (2018, p972) the Scottish Government claim their policies are evidence informed but their record is patchy at best. It would appear that those within the GTCS responsible for writing its documents have at least drawn on some research and evidence, but the exact nature and extent of this research and evidence is not clear, and its documents are certainly not as well references as they might be, or it could be argued, ought to be. Echoing Sachs, one of the attributes listed by Hamilton is that teachers should be “autonomous while recognising their place within the system”. Hamilton describes a new hybrid form of professionalism which encompasses a professional wish for empowerment, innovation, and autonomy but recognises the public need for quality assurance and accountability.

By adopting a hybrid model of professionalism there is clearly then scope for different interpretations in the balance between the aspects of the hybrid, and a tension between more managerial or more transformative conceptions of professionalism, as indeed there is in the interpretation and use of standards themselves. Some would argue that the use of standards to define what it means to be a teacher as a list of skills and minimum competences encourages an imposed reductionist, managerial approach to professionalism resulting in too much emphasis on accountability (Patrick et al., 2003) which promotes performativity, something that can have a profound distorting effect on professional behaviours (Priestley & Bradfield, 2021, p3). However, it can be argued that in Scotland the GTCS professional standards privilege a conception of ‘teacher as enquirer’ who engages critically with research and evaluation both individually and collaboratively (GTCS, 2012c, p12). This together with the aspirational nature of the Standard for Career-long Professional Learning (GTCS, 2021a) suggests a transformational conception of teacher professionalism. This appears to be borne out at least to some degree in practice. In its longitudinal study of the introduction of professional update (GTCS, 2020) the GTCS states “The Standard for Career Long Professional Learning is singled out as the most useful by respondents as it provides a broad and varied framework to enhance teacher professionalism” (p7). However, there are clearly still issues within the culture of Scottish education in terms of the understanding and practising of teacher agency and autonomy as this study also highlights that “Many respondents indicated their perception was that professional learning is ‘done to teachers’ to meet the needs of school improvement rather than being generated from their own practice” (p10) and whilst the majority to respondents indicated they had professional autonomy there was also evidence that although many had identified the next-steps in their professional learning journey through the professional review and development (PRD) process this was then changed by other school priorities being given priority.

It is clear, that regardless of the nature and purposes of the professional standards, the culture in which many Scottish teachers find themselves is not one of transformative professionalism, and it is not one which permits effective teacher agency; the dominant conception of professionalism appears to be managerial. Nevertheless the status of teachers, standards of professionalism, and public respect for those standards are all strong features of Scottish education (Murphy & Raffe, 2015, p153). As was described by Hargreaves and Goodson (1996, p3) teacher professionalism as currently manifest in Scotland appears to be continuing to advance in some respects but to be in retreat in others, and in part this may come down to a simple distinction between rhetoric and reality.

References

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The Forms of Capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood Press.

Boylan, M., Adams, G., Perry, E., & Booth, J. (2023). Re-imagining transformative professional learning for critical teacher professionalism: a conceptual review. Professional Development in Education, 1–19.

Commission on School Reform. (2022). Submission to the National Discussion on Education .

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education. Simon & Brown.

Downie, R. S. (1990). Professions and Professionalism. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 24(2), 147–159.

Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What Is Agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023.

Gewirtz, S., Mahony, P., Hextall, I., & Cribbs, A. (2009). Policy, professionalism and Practice: Understanding and enhancing teachers’ work. In S. Gewirtz, P. Mahony, I. Hextall, & A. Cribbs (Eds.), Changing Teacher Professionalism: International trends, challenges and ways forward (pp. 3–16). Routledge.

GTCS. (n.d.). About Us – The General Teaching Council for Scotland. Retrieved 7 October 2023, from https://www.gtcs.org.uk/about-us/

GTCS. (2012). The Standards for Registration: Mandatory Requirements for Registration with the General Teaching Council for Scotland.

GTCS. (2017). GTCS Position Paper: Teacher Professionalism and Professional Learning in Scotland.

GTCS. (2020). Professional Update Longitudinal Study Sessions 2014 – 19.

GTCS. (2021a). The Standard for Career-Long Professional Learning: An Aspirational Professional Standard for Scotland’s Teachers.

GTCS. (2021b). The Standard for Full Registration: Mandatory Requirements for Registration with the General Teaching Council for Scotland.

Hamilton, T. (2018). The General Teaching Council for Scotland as an Independent Body – But for How Long? In T. G. K. Bryce, W. Humes, D. Gillies, & A. Kennedy (Eds.), Scottish Education (5th ed., pp. 873–883). Edinburgh University Press.

Hargreaves, A. (2000). Four Ages of Professionalism and Professional Learning. Teachers and Teaching, 6(2), 151–182.

Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional capital: transforming teaching in every school. Routledge.

Hargreaves, A., & Goodson, I. (1996). Teachers’ Professional Lives: Aspirations and Actualities. In Teachers’ Professional Lives (pp. 1–27). RoutledgeFalmer.

Hargreaves, A., & O’Connor, M. T. (2018). Collaborative professionalism : when teaching together means learning for all. Corwin.

Humes, W., Bryce, T. G. K., Gillies, D., & Kennedy, A. (2018). The Future of Scottish Education. In T. G. K. Bryce, W. Humes, D. Gillies, & A. Kennedy (Eds.), Scottish Education (5th ed., pp. 969–979). Edinburgh University Press.

Kennedy, A., Barlow, W., & MacGregor, J. (2012). ‘Advancing Professionalism in Teaching’? An exploration of the mobilisation of the concept of professionalism in the McCormac Report on the Review of Teacher Employment in Scotland. Scottish Educational Review, 44(2), 3–13.

Kolsaker, A. (2008). Academic professionalism in the managerialist era: a study of English universities. Studies in Higher Education, 33(5), 513–525.

Murphy, D., & Raffe, D. (2015). The governance of Scottish comprehensive education. In D. Murphy, L. Croxford, C. Howieson, & D. Raffe (Eds.), Everyone’s Future: Lessons from fifty years of Scottish comprehensive schooling (pp. 139–160). Institute of Education Press.

OECD. (n.d.). OECD – Education. Retrieved 7 October 2023, from http://www.oecd.org/education/

Patrick, F., Forde, C., & McPhee, A. (2003). Challenging the ‘New Professionalism’: from managerialism to pedagogy? Journal of In-Service Education, 29(2), 237–253.

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher Agency. Bloomsbury.

Priestley, M., & Bradfield, K. (2021). Educational governance through outcomes steering: ‘reforms that deform’. The Scottish Greens.

Rowland, T. (2013). The Knowledge Quartet: The genesis and application of a framework for analysing mathematics teaching and deepening teachers’ mathematics knowledge. Journal of Education, 1(3), 15–43.

Rowland, T., Huckstep, P., & Thwaites, A. (2005). Elementary Teachers’ Mathematics Subject Knowledge: the Knowledge Quartet and the Case of Naomi. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 8(3), 255–281.

Sachs, J. (2003). The Activist Teaching Profession. Open University Press.

Sachs, J. (2016). Teacher professionalism: why are we still talking about it? Teachers and Teaching, 22(4), 413–425.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. Basic Books.

Scott, D. (2000). Reading Educational Research and Policy. Routledge.

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14.

Watson, C., & Fox, A. (2015). Professional re-accreditation: constructing educational policy for career-long teacher professional learning. Journal of Education Policy, 30(1), 132–144.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

Whitty, G. (2008). Changing modes of teacher professionalism: traditional, managerial, collaborative and democratic. In B. Cunningham (Ed.), Exploring Professionalism (pp. 28–49).

Leave a comment