At an early stage of my reading for my PhD into the professional learning of teachers in Scotland, I considered the main policy developments affecting teacher professional learning in Scotland. This helped me identify key issues for me to explore in my subsequent research. My description and basic analysis of the policy background from the Main Review in 1986 through to the OECD review of Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) in 2021 and the resulting reviews and reports is given below.

A significant resource facilitating the research of educational developments in Scotland are the five editions of Scottish Education (Bryce et al., 2013, 2018; Bryce & Humes, 1999, 2003, 2008). These provide a rich source of information and analysis of the main developments in Scottish education, both from a perspective of the time of each edition plus with an element of hindsight in subsequent editions.

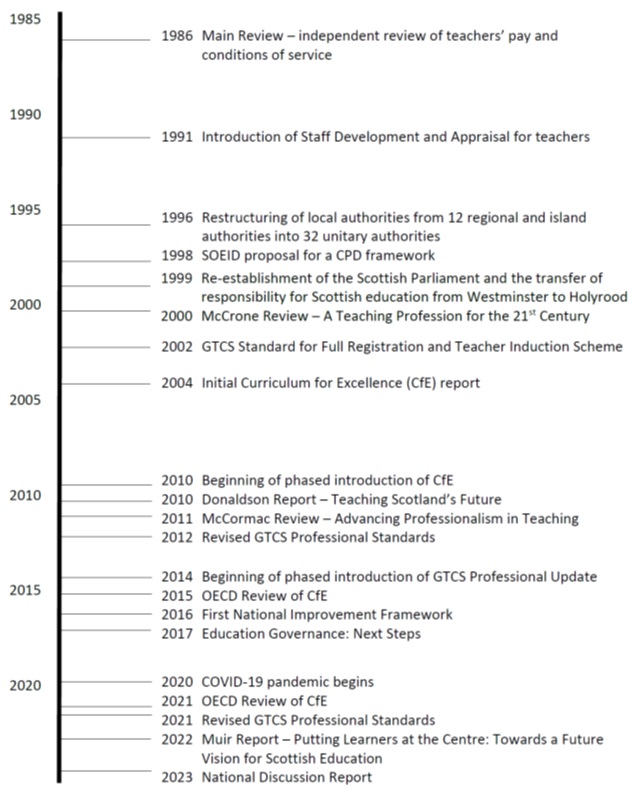

The timeline of the major policy developments described and analysed is shown below.

1. The context for, and history of, teacher professional learning in Scotland up to 1999

Scotland has long had a distinctive education system. On the union of Scotland and England in 1707, along with its legal system and church, Scotland retained its own education system, albeit governed from Westminster, via the Scottish Office (Anderson, 2018; Gillies, 2018b, p108). Historically, Scots have been proud of their education system and its ‘lad o’ pairts myth’, whereby any child with aptitude and ability has access to an education which can allow that individual to flourish, although this idealised perception is not necessarily supported by evidence (Anderson, 2018, p99; Humes & Bryce, 2018, p119).

Education has been relatively highly valued in the Scotland, and there has been legislation to provide a national system of local schools with salaried teachers for over 300 years, which has historically placed teachers in relatively high regard within Scottish society. The roots of teacher education can be traced back to the middle of the 19th Century and the work of David Stow and the formation of the Educational Institute of Scotland (EIS). This was strengthened following the Education Scotland Act of 1872 when attendance at school was made compulsory, and the need for more teachers increased the recognition of the need to ‘train’ teachers. However, the main focus of teacher education remained firmly on initial teacher education (ITE) with in-service training, continuing professional development (CPD) and career-long professional learning (CLPL) only growing in importance in relatively recent times (Gatherer, 2013; Kennedy, 2018; MacDonald & Rae, 2018).

Through much of the 20th Century until the 1980s, colleges of education were funded by central government to provide ‘free’ in-service training for teachers. This was very much a provider-led system with the providers deciding on the ‘training’ available and whether teachers participated in this being very much up to the individual rather than there being any systemic expectation. In the 1980s and 1990s, as part of the more general political changes under a Conservative government which had been in power for some time, often with a relatively weak opposition, more funding and greater decision-making powers were devolved to schools. This was accompanied by the introduction of a more business-oriented approach to education with an emphasis on central controls, target-setting, and quality management approaches. The government funding for colleges of education to provide in-service training was ended. The inquiry into teachers’ pay and conditions of service, led by Sir Peter Main (Main, 1986) following an extended period of teacher industrial action from 1984 to 1986, recognised the importance of regular and systematic professional learning based in schools, and that the starting point for such professional learning should be the assessment of need via teacher appraisal. The settlement following the Main Report resulted in the introduction of five in-service days per annum and 50 hours of planned activity time (PAT) in school but outwith normal teaching hours. As a result, professional learning became more school-led, and the control of this teacher professional learning time under the control of schools. This had the advantages of giving the potential for professional learning to be better matched to school priorities and there was an expectation that all teachers be involved in professional learning rather than it being voluntary activity for a minority. A national programme of appraisal training was rolled-out across the country during the early-1990s training teachers how to appraise and be appraised (Marker, 1999, p920; SOED, 1991). However, this introduced a tension between teachers identifying their own individual professional learning needs through appraisal and the professional learning being provided being matched to whole school development planning (Marker, 1999, p922). The school-led professional learning was not generally held in high regard by teachers, provision was often fragmented, beyond-school professional learning opportunities were now probably fewer than previously, and teachers wishing to engage in the opportunities available were likely to have to do so in their own time and at their own expense (Marker, 1999, p921).

To further complicate matters, in 1996 the 12 regional and island education authorities were restructured into 32 local authorities. Their smaller size, and it being a time of financial stringency, meant that the level of central support available to schools and teachers, such as through subject advisory services, was much reduced. Those staff who remained also tended to take on greater accountability-driven quality assurance roles, rather than the more supportive, advisory ones previously, as what Gatherer (2013) called “adspectors” (p981). The net effect was that most of the professional learning available was focussed on management and appraisal training and not on teaching and learning. This promoted a very managerial conception of teacher professionalism. Even with the introduction of appraisal training, implementation was limited, as described by Marker (1999):

“the authorities have been forced to soft-pedal on the implementation because of the resource implications: the cost in staff time and the difficulties in providing appropriate support once needs have been identified”. (p920)

This scenario, may explain, at least in part why, Watson and Fox (2015) report, two decades after its introduction, that the take up in appraisal, or professional review and development as it became known, has been “undeniably patchy both in terms of overall implementation and the rigour with which it is pursued” (p135). By the 1990s professional learning had still not become an established and recognised part of the identity of being a teacher in Scotland. Teachers had not been willing to campaign for it at the expense of salaries and other conditions of service such as reduced class sizes, and local authorities had regularly sacrificed it in order to meet their other statutory duties, and government, despite advocating for it, had not provided the necessary resources for it (Marker, 1999, p924), all situations that could be argued continue to the present day and result in a continued separation of rhetoric from reality.

Alongside the developments in appraisal, including the introduction of staff development coordinators in schools (O’Brien & MacBeath, 1999), there was consideration of introducing a framework of continuing professional development for teachers in Scotland (SOEID, 1998; Sutherland, 1997), and although this did not result in a formal framework it inevitably informed that which followed.

2. Developments during the 21st century

The prominence of education in the political discourse in Scotland has been raised since 1999 as education is one of the main policy areas devolved to the Scottish Parliament. Due to the constitution of the Scottish Parliament, with its members elected on a proportional representation basis, coalition and minority government has maintained an element of consensus politics and a relatively conservative approach to policy development. Historically, Scottish education has been governed through a combination of firm central direction of policy together with the delegation of the responsibility for implementation to local authorities which provides an element of local democratic accountability (Humes & Bryce, 2018, p120). The Scottish National Party (SNP) has now been the party of central government since 2007. It could be argued, as is common with political parties which have been in power for an extended period with a relatively weak opposition, there are signs of tensions in the established status quo, and at times a frustration with some local authorities in their implementation of national policy. Recent developments show signs of increased centralisation and authoritarian tendencies within central government and attempts to weaken the role of local authorities. Attempts to reduce the role and power of local authorities can be seen in moves to give greater devolved power and responsibilities to headteachers, and the formation of the regional improvement collaboratives (RIC) (Bryce & Humes, 2018b, p47; Redford, 2018, p175).

Nevertheless there has been a broad consensus and support for education to be a key lever to improve disadvantage through policies such as providing free school meals, increased early years provision, and free university tuition (Gillies, 2018a). This broadly social democratic approach to education policy has continued since the devolution of responsibility for education to the Scottish Parliament in 1999 regardless of the party or parties in power, with an emphasis on community, inclusion and equality (Hulme & Kennedy, 2016; Humes & Bryce, 2018). For education to be a lever of change in this way it is therefore essential that the teaching workforce develops, and appropriate professional learning be available to support change.

During the 21st Century there have been several major policy developments in Scottish education, which have had an impact on teacher professional learning to some degree. These have included: the McCrone Report (McCrone, 2000), and its subsequent agreement (SEED, 2001); Curriculum for Excellence (Curriculum Review Group, 2004); the Donaldson Report (Donaldson, 2010); the McCormac Report (McCormac, 2011); the introduction of a suite of GTCS professional standards (GTCS, 2012a, 2012b, 2012c) and their revision (GTCS, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c, 2021d); the National Improvement Framework (Scottish Government, 2016a), and various developments in educational governance (Scottish Government, 2017, 2019c).

2.1 McCrone

During the 1990s there was growing discontent within the teaching profession at the continuing decline in the real values of the salaries won during the industrial action that led to the Main Report (Main, 1986) and subsequent agreement. Within the new government in the devolved Scottish Parliament there was a desire to avoid a return to industrial action by the teaching profession. As a result, Professor Gavin McCrone was appointed to lead an inquiry into teachers’ pay and conditions of service. The findings of this inquiry were reported in what was commonly referred to as the McCrone Report (McCrone, 2000). The McCrone Report was used by the various stakeholders involved as the starting point for a negotiated agreement (SEED, 2001), frequently referred to as the McCrone Agreement, and somewhat confusingly given the same title as the McCrone Report. This agreement did not include all recommendations as originally stated in the McCrone Report, but the basic principles were taken forward including a recognition of the need for professional learning, and improved induction arrangements for new teachers. McCrone had described the current situation with regard to the induction of new teachers as “little short of scandalous” (McCrone, 2000, p7). The McCrone agreement included:

- for new teachers, a guaranteed induction year with a 0.7 full-time equivalent timetable, along with mentoring and professional learning support in place of the previous two-year probationary period with no guaranteed mentoring or professional learning

- for teachers in general, an entitlement to 35 hours of professional learning per annum and an annual professional review

- the introduction of the chartered teacher scheme designed to recognise and reward teachers who wished to develop their careers by staying in the classroom rather than following a management or leadership path.

Together with the Scottish Qualifications for Headship for teachers aspiring to school leadership and arrangements for professional review and development this provided what was in effect a ‘CPD framework’ covering all career stages (Kennedy, 2013; Purdon, 2003). The Main Report (Main, 1986) had initiated the process of establishing the concept of professional learning being central to the identity of being a teacher. The Sutherland Report (Sutherland, 1997) had recommended a ‘CPD framework’, and although this had not been acted upon, such a framework, to all intents and purposes, emerged as part of the McCrone agreement (SEED, 2001). The remit of the GTCS was also expanded from covering disciplinary issues, entry to teaching, and initial teacher education to also cover career-long professional learning. Within this framework, CPD was defined as:

“The range of experiences that contribute to teacher development is very wide and should be recognised as anything that has been undertaken to progress, assist or enhance a teacher’s professionalism. When planning CPD activities, teachers and their managers should consider the particular needs of the individual, whilst taking account of school, local and national priorities”. (SEED, 2003, p3)

Agreement was reached following the McCrone inquiry largely because it resulted in significantly increased teacher salaries which redressed the decline since the Main review. This continued a recurring trend in teacher salaries over several decades where gradual declines are redressed following dispute, an inquiry, and the agreement of a significant salary increase (Forrester, 2003, p1013). There continued to be mixed messages about the nature of teacher professionalism in Scotland post-McCrone. Professional learning primarily remained based on, or perceived as, attending ‘courses’ and professional learning to be seen as something provided for, and delivered to teachers (Purdon, 2003, p946). School-led professional learning promoted flexibility but nonetheless there were, and indeed still are, expectations that government priorities should be achieved. Within the McCrone agreement (SEED, 2001, Annex B) there was also an emphasis on teachers performing tasks, including undertaking professional learning, as directed by and with the agreement of the headteacher, calling into question the level of autonomy and agency expected of and available to teachers. A focus on standards and competencies, reinforced by the technicist language of the inspection framework How Good Is Our School? (HGIOS) which was first introduced by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Education in 1996 (Education Scotland, 2015). This all implied a business model of education and a managerial conception of teacher professionalism dominated by target-setting and performance management measures. However, McCrone also promoted collegiality implying a more transformative conception of professionalism, but as Macdonald (2004, p432) commented, a more radical change in policy was needed in order to create an environment in which Scottish teachers had the time and inclination to adopt a more activist approach required for such collegiality. More radical policy change would also be necessary for there to be more individualist forms of teacher accountability from within the profession rather than accountability imposed on the teaching profession from outside. The passage of time, international policy developments, and the subsequent content of the Donaldson Report (Donaldson, 2010) largely supported travel in this direction but as before policy messages remained somewhat mixed and continued to, explicitly or otherwise, promote a limited conception of teacher professionalism.

In the years post-McCrone the importance of teacher professional learning as a means of improving education system performance was increasingly recognised. This was driven partly by the increase in prominence of international comparison studies such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) (OECD, 2018), Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) (IEA, 2019) and by a number of influential organisations, such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and McKinsey & Company, and their reports (Barber & Mourshed, 2007; Mourshed et al., 2010; OECD, 2005). Statements such as “raising teacher quality is perhaps the policy direction most likely to lead to substantial gains in school performance” (OECD, 2005, p23), and “The quality of an education system cannot exceed the quality of its teachers” (Barber & Mourshed, 2007, p16) and “The only way to improve outcomes is to improve instruction” (Barber & Mourshed, 2007, p26) became commonplace in the discourse around school improvement and professional learning, as did the practice of ‘policy borrowing’ from countries seen to be high performers in the international comparison studies. It was also driven partly by a growing body of research and evidence on school improvement which showed that the quality of teaching had a very significant influence on the attainment of pupils (Hattie, 2003). As many teachers have a career of two decades or more in the classroom, it was increasingly believed that the quality of their teaching, and therefore the performance of an education system overall, could only be improved through effective career-long professional learning.

2.2 Donaldson, McCormac, and the GTCS professional standards and professional update

A decade or so after the McCrone Report, and relatively soon after the SNP came to power in Holyrood, the Scottish Government commissioned two inquiries which led to two influential reports, the Donaldson Report (Donaldson, 2010) into teacher education, and shortly afterwards the McCormac Report (McCormac, 2011) into teacher employment. Both had very significant implications for teacher professional learning. The remit given to Graham Donaldson, who had recently retired as Her Majesty’s Senior Chief Inspector of Education, was “To consider the best arrangements for the full continuum of teacher education in primary and secondary schools in Scotland. The Review should consider initial teacher education, induction and professional development and the interaction between them.” (Donaldson, 2010, p106). Donaldson was seen by many as an ‘insider’ within Scottish education and in an unusual move was not the chair of an inquiry group but given sole responsibility to conduct the inquiry. Professor Gerry McCormac on the other hand had spent most of his working life outwith Scotland and was chair of an inquiry group. This group was tasked with reviewing the McCrone agreement with a remit “To review the current arrangements for teacher employment in Scotland and make recommendations designed to secure improved educational outcomes for our children and young people” (McCormac, 2011, p60). This review was announced by Michael Russell, the Cabinet Secretary for Education, as part of the budget agreement reached between the Scottish Government and the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities which also included a pay freeze for teachers, changes to supply teachers’ pay and conditions, a loss of salary conservation, and changes to probationers’ conditions, all in the wake of the global financial crash of 2008 (Buie, 2011; Humes, 2013).

The Donaldson Report was a comprehensive review of teacher education across initial teacher education, early career, career-long, and leadership phases. It contained fifty recommendations targeted across many stakeholders in Scottish teacher education. In what is fairly unique with such a review, but perhaps not surprisingly given Donaldson’s standing within Scottish education’s policy community, the Scottish Government accepted all fifty of the recommendations, the vast majority in full, but with a few in principle or in part (Scottish Government, 2011b), although it was the responsibility of many other organisations to implement and deliver many of these recommendations, and it took some time before progress was made in some areas (Buie, 2012) and Donaldson himself has commented that much in his report remains to be implemented (Chapman & Donaldson, 2023, p9).

Donaldson has had a significant impact on shaping the nature of professional learning since, making it clear that on completion of initial teacher education, teachers are not the finished article and require ongoing career-long professional learning. Donaldson was explicit in his report of his desire to enhance and reinvigorate the professionalism of teachers in Scotland (Donaldson, 2010, p10) but was not explicit in defining the nature of this professionalism only that it needed to be “reconceptualised” (Donaldson, 2010, p97). By not defining professionalism there is an implicit inference that the reader has a shared understanding of how the term is being used, but the language used by Donaldson sends mixed messages about the nature of the professionalism envisaged. For example, repeated mentions are made to teachers developing and improving their “skills and competencies” which reflects quite technicist language representing a managerial conception of professionalism. However, Donaldson also promotes collaborative working in local teams, professional networking, a move away from top-down local authority-led professional learning events, and a “vision of teachers as increasingly expert practitioners whose professional practice and relationships are rooted in strong values, who take responsibility for their own development” (p15) representing a much more transformative conception of professionalism. Kennedy and Doherty (2012) used critical discourse analysis to investigate the use of the term professionalism by Donaldson in his report. They identified that it is used and qualified in seven different ways: extended professionalism; enhanced professionalism; reinvigoration of professionalism; redefined professionalism; wider concept of professionalism; reconceptualised model of professionalism, and twenty-first century professionalism. They identified that the first six of them imply an implicit criticism of the current nature of teacher professionalism. They went on to contrast this deficit view of teachers’ current enactment of professionalism as being somewhat in contradiction to the generic statements made by Donaldson report about the high quality of teachers in Scotland. The exact meaning of the seventh use, ‘twenty-first century professionalism’, is vague at best. It is clear from this analysis, that despite the statements supportive of a more transformative conception of professionalism, and the overwhelmingly positive response to the Donaldson report with very little dissent in the teaching profession about the direction of travel, the dominant conception of professionalism in the Donaldson report is a managerial one, perhaps not altogether surprising since Donaldson’s previous career was Her Majesty’s Senior Chief Inspector of Education. Kennedy and Doherty (2012) concluded:

“In appealing to particular standards of ‘professional’ behaviour, we contend that the concept of professionalism is being mobilised in the Report, intentionally or otherwise, as a form of subtle control over teachers and teacher education. We therefore propose that one reading might be that rather than being the answer or panacea, the focus on professionalism has more to do with the desire to influence teachers and teacher education than it does to engage with a particular ideological understanding or practical enactment of professionalism.” (p843)

Following the Donaldson Report the General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS) reviewed its standards introducing a suite of revised professional standards for teachers. In addition to the Standard for Registration (GTCS, 2012c), a requirement to teach in Scotland, this included for the first time the Standard for Career-long Professional Learning (GTCS, 2012a), which was an evolution from the previous Standard for Chartered Teachers and fulfilled the role of the Standard for Active Registration proposed by Donaldson (Donaldson, 2010. p98). The Standard for Chartered Teachers was no longer required as this grade of teacher was removed in the agreement following the McCormac inquiry. This standard emphasised the change in terminology from continuing professional development (CPD) to career-long professional learning (CLPL) in official documentation related to the professional learning of in-service teachers in Scotland, and with it the subtle change in messaging away from CPD which carried with it some historical baggage towards a greater emphasis on ‘learning’. The Standard for CLPL was also different in nature to the Standard for Registration as it was aspirational rather than mandatory in nature and not something teachers were necessarily expected to ‘achieve’ (Kennedy, 2016). The suite of GTCS standards also included the Standard for Leadership and Management (GTCS, 2012b), aimed at those in both middle and senior leadership positions in schools. All of the standards in this suite placed greater emphasis than previously on teacher leadership, professional enquiry, teachers using research and evidence-informed practices, and greater expectations of professional agency. They thus go beyond the traditional views and criticisms often levelled at competency standards (Watson & Fox, 2015, p134) which are characterised by a managerial conception of professionalism. The GTCS suite of standards includes aspects which are clearly more aligned with collaborative, democratic, or transformative conceptions of professionalism. If such aspects can dominate those with a narrow managerial accountability focus this could result in standards of the nature described by Christie and Kirkwood (2006):

“a well-grounded standards framework might be an opportunity for professionals to take control of the process of self-definition or, to … ‘restory’ themselves. Indeed, such a framework may be desirable and even a necessary context for both the empowerment of teachers and the enhancement of their professionalism.” (p266)

Donaldson also recommended the setting up of a virtual college of school leadership to improve leadership capacity at all levels in Scottish education (Donaldson, 2010, p101). The Scottish College for Educational Leadership (SCEL) was set up to co-ordinate and deliver support programmes in teacher, middle, school and system leadership, although it was subsequently absorbed into Education Scotland (Education Scotland, n.d.) as its professional learning and leadership team. The OECD review of Scottish education also recommended that “a coherent strategy for building teacher and leadership social capital” be developed (OECD, 2015, p140). Social capital is built through effective collegiate and collaborative working and quality interactions between people (Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012, p90) and this has been a focus of the work of SCEL and its successor, and this is certainly consistent with promoting a more transformative conception of professionalism.

The McCormac Report followed soon after the Donaldson Report was published, and Donaldson was also a member of the McCormac review group. The focus of this report was teachers’ pay and conditions of service and it revisited many of the issues addressed by McCrone a decade earlier. On a surface level, or from its title at least, it followed on from McCrone and Donaldson and further endorsed the need for teachers to build knowledge and professional understanding over time through professional learning, although without going into any detail of what this might look like in practice. Likewise the report does not articulate explicitly what is meant by the term professionalism. Kennedy, Barlow and MacGregor (2012) used critical discourse analysis to investigate the use of the term professionalism in the McCormac Report and conclude it is overwhelmingly used in a managerial manner implying a deficit view of the current state of teacher professionalism. In several instances in the McCormac Report the term professionalism is used with varying degrees of subtlety as a means of influencing control over the teaching profession, for example:

“We believe that the quality of the teaching profession is paramount and the capacity for schools and local authorities to utilise professionalism in a flexible manner will ensure the best possible educational outcomes for our children and young people.” (McCormac, 2011, p52)

This is analysed by Kennedy, Barlow and MacGregor (2012) thus:

“The idea that professionalism can be ‘utilised’ by schools and local authorities in a ‘flexible manner’ implies a very explicit and intentional attempt at using the concept of professionalism to impose control over teachers and their work. This is a clear and unambiguous example of a managerial conception of professionalism; one where to be professional is to be compliant.” (p7)

This is promoting professionalism in a manner consistent with what Hargreaves and Goodson (1996, p20) describe as a “rhetorical ruse – a way to get teachers to misrecognize their own exploitation and to comply willingly with increased intensification of their labour in the workplace” or what Menter (2009, p221) describes as “the deep irony of these processes of curtailing the independence and autonomy of teachers is that they are usually presented within a discourse of professionalization”. The McCormac report appears to be a prime example of hegemony in action, and Kennedy, Barlow and MacGregor (2012) go as far as to suggest that rather than being entitled “Advancing Professionalism in Teaching” the McCormac Report would have been more appropriately entitled “Teachers’ Pay and Conditions: A Spending Review” (p10) as the real drivers behind the report were financial rather than those of advancing professionalism. It is now clear that McCormac was, driven by, or at least substantially overshadowed by, financial concerns in the wake of the global financial crash of 2008 rather than a central concern to enhance the quality of professional learning and of professionalism. Where Donaldson and McCormac proposed different options on overlapping issues the government of the day tended to side with the cheaper option, such as the ending of the chartered teacher scheme as proposed by McCormac rather than the reformed version proposed by Donaldson (A. Kennedy, 2013, p930).

The McCormac Report made numerous references to the recommendations of the Donaldson Report and endorsed many of them, such as “Teachers should have access to relevant high quality CPD for their subject and other specialist responsibilities” (Donaldson, 2010, p100; McCormac, 2011, p21). It also endorsed the GTCS’s plan to introduce professional update (GTCS, n.d.), a professional reaccreditation scheme whereby teachers have to maintain an online professional learning log which is approved and signed-off by the teacher’s line-manager every five years. This went further than Donaldson’s recommendation that teachers merely maintained an online profile of their professional learning (Donaldson, 2010, p99). The process of annual professional review and development, which had developed from the original appraisal processes introduced in the 1990s, plus the five yearly professional update further highlighted the entitlement of teachers to ongoing professional learning, but also raised issues around the capacity of the system to be able to deliver appropriate professional learning, as well as the level of bureaucracy and accountability involved. The wording used in the McCormac Report emphasised the accountability aspect of re-accreditation rather than that of professional growth of teachers “we strongly support the GTCS in its plans to introduce a system of re-accreditation, or ‘professional update’, that would help ensure teachers are maintaining and developing their skills” (p20). Professional update was introduced with “remarkably little resistance, or even notice, from practitioners” (Watson & Fox, 2015, p136). Watson and Fox attribute this to the GTCS’s very successful management of its introduction with the consultations on professional update only having questions relating to process rather than principle, the processes of professional review and development and reaccreditation being successfully disassociated from ‘fitness to teach’ processes, an emphasis on the developmental function of professional update and professional review and development, and the considerable charm offensive by GTCS CEO Tony Finn in selling professional update as irrefutable common sense. However, they conclude that in introducing professional update:

“GTCS has elided the improvement and accountability functions in a process which has successfully deflected attention from the question of competence and promoted the process as an entitlement, while simultaneously enabling the GTCS to exert a more centralised form of authority not just on the profession overall but on each and every individual, as the entrepreneur of self, within it.” (p142)

It could therefore be argued that the GTCS, through both its professional standards and the professional update process, continues the mixed conceptualisation of professionalism exhibited in other policy developments with elements of both managerial and transformative conceptions of professionalism but has also ensured the continuation of a centralising tendency in its power relationship with the profession it is responsible for regulating. It is nevertheless clear that its professional standards and the professional update process place a high value on the importance of professional learning for teachers, and an emphasis on it being an entitlement of teachers to engage in transformative professional learning practices such as the enquiry and research-informed practices with the values of integrity, trust and respect at the heart of being a teacher in Scotland (GTCS, 2012c). However, the annual professional review and development process which is integral to professional update results in an individual professional learning plan for each teacher. Unlike in many countries, in Scotland it is not required for this to be linked to a school professional learning plan (OECD, 2022, p391). This continues to allow a potential disconnect between a teacher’s professional learning and that consistent with the content of the teacher’s school’s improvement plan.

How much of the change in the culture and practices in teacher professional learning that has occurred in the decade since Donaldson and McCormac, or from more general societal, professional, or international changes and pressures is difficult to judge; there has been very little research on the matter (A. Kennedy & Beck, 2018, p849). In a Scottish Government commissioned evaluation of the impact of the implementation of the Donaldson Report (Black et al., 2016), conducted by a market research company, it was reported “that there has been a significant shift in the culture of professional learning“ (p89) and according to the teacher self-reported data on which the evaluation was based that this shift was demonstrated in four key areas:

- Teachers are more engaged with professional learning

- There is a greater focus on the impact of professional learning on pupils

- Teachers are engaging in professional dialogue more often

- Teachers show a greater willingness to try new approaches than five years previously.

However, this evaluation went on to report that “there was widespread acknowledgement – across the teaching profession and among LA and national stakeholders – that there is a considerable way to go before the vision set out in TSF [Teaching Scotland’s Future – the Donaldson Report] is fully realised” (p91).

2.3 Curriculum for Excellence

Teacher professional learning policy and its development does not exist in a vacuum, and curriculum development has a very significant influence on the professional learning needs of teachers, as stated by (Stenhouse, 1975) “curriculum development must rest on teacher development” (p24). The introduction of Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) (Curriculum Review Group, 2004) aimed to reduce the specificity of the curriculum guidelines and devolved greater decision-making in curriculum content and structures to schools and teachers (OECD, 2015, p121).

The philosophy of CfE emphasised teachers as agents of change and co-creators of the curriculum, not something that had been a strong feature of the previous curriculum and implying a need for professional learning. Some had describing Scottish teachers as having been ‘de-professionalised’ and ‘de-skilled’ as a result of having been treated like technicians rather than professional educators (Gatherer, 2013, p979), a phenomenon that had also been observed in other education systems (OECD, 2017). Exhibiting a mixture of conceptions of professionalism, the philosophy of CfE promotes greater teacher autonomy (Scottish Government, 2008, 2011a; SNCT, 2007) at the same time as greater collaboration between teachers and with other partners, and a shift in culture regarding how teachers expect, and are expected, to account for their professional learning (Kennedy, 2013, p935). This inevitably raises questions about the nature of the professional learning teachers require for the successful implementation of CfE, and how that be best provided during a time of financial austerity. Despite widespread political and professional support for the principles of CfE, the path of its implementation had not been smooth (Drew, 2013; Priestley, 2018; Priestley & Minty, 2013). The Scottish Government commissioned a review of CfE which was conducted by the OECD. The resulting report (OECD, 2015) made twelve recommendations including: creating a new narrative for CfE; strengthening the professional leadership of CfE and the ‘middle’ (without defining clearly what was meant by the middle), and developing a coherent strategy for building teacher and leadership social capital. The immediate response was the writing of an additional layer of curriculum guidance, the CfE Benchmarks (Education Scotland, 2017), seen by some as welcome clarification and guidance, but others as yet another layer of bureaucracy diminishing teacher autonomy and the scope for teacher agency. A refreshed narrative for CfE did not appear until 2019 (Scottish Government, 2019e), and was met with somewhat mixed reviews and support (Humes, 2019; Priestley, 2019). At its outset CfE promised a radical change in curriculum and pedagogical approaches requiring significant teacher professional learning to enable such changes to be implemented and embedded in practice. In the years since, during times of relative austerity, there has been a lack of clarity of purpose, especially in the Senior Phase of CfE, which has inevitably impacted on the quality, quantity, and nature of the professional learning available and seen as desirable, both by teachers and education system leaders.

After many years of continual curriculum and assessment changes, some would say ‘fudges’ (Murphy & Raffe, 2015, p155), in the Senior Phase and ongoing concerns from many quarters (Learned Societies’ Group on STEM Education, 2016, 2019; Scottish Government, 2016c; Scottish Parliament, 2018, 2019; SSTA, 2017), following a successful motion in the Scottish Parliament by opposition parties, another independent review by the OECD was announced (Scottish Government, 2019d). In its second report, the OECD (2021) again included twelve recommendations all of which the Scottish Government accepted immediately (Scottish Government, 2021b) and initiated a process leading to further reviews and reports (Campbell & Harris, 2023; Muir, 2022). Whilst praising the general aspirational nature of CfE the OECD identified several issues preventing these aspirations being realised fully. They described education in Scotland as being highly politicised, and perhaps because of this, there being a policy environment lacking in coherence where roles and responsibilities for those throughout the system were not clear in relation to CfE. The OECD also highlighted the very high teacher contact hours in Scotland compared to other countries which reduced teachers’ capacity to lead, plan and support curriculum planning and the monitoring of student achievement (OECD, 2021, p97). This will inevitably also compromise the ability to plan and implement teacher professional learning to address issues which might have been uncovered if teachers were better able to fulfil such activities.

It would be hard to argue that the initial promise of CfE has been fully realised. It would also be hard to argue that there has been any significant change away from a culture of managerial professionalism towards one of transformative professionalism that the opportunity presented by the introduction of CfE both provided and demanded, especially in relation to the Senior Phase in secondary schools. The OECD’s description of a “busy system at risk of policy and institutional overload” (OECD, 2021, p12) and a lack of policy coherence within the Scottish education system inevitably also applies to the professional learning of teachers. One of these many policy developments, first introduced in the year after the 2015 OECD review of CfE, and following widespread consultation, was the National Improvement Framework (NIF) (Scottish Government, 2016a).

2.4 The National Improvement Framework

In theory, the National Improvement Framework should assist with policy coherence and its stated aim is to “bring together an enhanced range of information and data at all levels of the system, to drive improvement for children and young people in early learning and childcare settings, schools, and colleges across the whole of Scotland” (Scottish Government, 2019e, p6). A draft version was published in September 2015 (Scottish Government, 2015), essentially for consultation, although the exact process and timescale for this was not made entirely clear (Learned Societies’ Group on Scottish Science Education, 2015). A finalised version was subsequently published in January 2016 (Scottish Government, 2016b), and the first of a series of annual updates (Scottish Government, 2016a) was published in December 2016. The National Improvement Framework aims to improve the strategic management of change in Scottish education by setting a small number of priorities for improvement, set within the broad vision of CfE. McIlroy (2018), using an exclamation mark for emphasis, wrote “A new National Improvement Framework was badly needed!” (p626), he also noted that the OECD fingerprints were evident in its priorities.

One of the six key drivers in the National Improvement Framework was teacher professionalism, and by December 2016 it listed a number of new and ongoing ‘improvement activities’ covering a range of initial teacher education and professional learning initiatives, and somewhat out of place in comparison, a statement about streamlining the guidance on CfE (Scottish Government, 2016a, p7). Whilst the recognition of the importance of improving teacher professionalism and professional learning for effecting system improvement was a positive development, the National Improvement Framework’s apparent approach to improvement being based closely on well-supported OECD evidence of success, this was rapidly undermined by the publication of a detailed, prescriptive, and rapidly paced delivery plan, illustrating a simplistic mechanistic conception of teaching and teacher professionalism (MacDonald & Rae, 2018, p838; McIlroy, 2018, p627). The deadlines set, and expected pace of change, perhaps reflecting more the period of political electoral cycles rather than that necessary to effect complex and lasting educational change as described by Robinson, Hohepa and Lloyd (2009), Timperley, Wilson, Barrar and Fung (2007) and others. This sent very mixed messages to the teaching profession, with its rhetoric of empowerment but also a tone of command, prescription, and control, particularly when compared to the tone of the likes of the Donaldson Report, the OECD review, and the principles of CfE.

2.5 Education Governance: Next Steps

Shortly after publishing the first National Improvement Framework, the Scottish Government published revised education governance proposals (Scottish Government, 2017). The title of the document was telling, “Education Governance: Next Steps, empowering our teachers, parents and communities to deliver excellence and equity for our children”. This is perhaps a prime example of what Bryce and Humes (2018a) describe as “the rhetorical prose so prevalent in much of the documentation issued by central government and the agencies associated with it” (p3).

This set out clearly the aim of trusting teachers as experts to shape the education they provide to young people (Scottish Government, 2017) “We will trust and invest in teachers and practitioners as empowered, skilled, confident, collaborative and networked professionals” (p23). It also led to the development of a Headteachers’ Charter (Scottish Government, 2019a, 2019b) which whilst emphasising the collaborative and collegiate nature of education nevertheless placed greater emphasis on headteachers’ autonomous decision-making powers. This move also diminished the influence of local authorities, reversing the greater autonomy given to local authorities when the Scottish National Party came to power in 2007 and signed a concordat agreement with the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (Cairney & McGarvey, 2013, p167). The local governance of education has been the responsibility of local authorities since 1929, and historically there has been a well understood division between central government setting the general policy direction and then the exemplification and implementation of policy within this central government guidance being the responsibility of local authorities. This has provided an element of local democratic accountability for education through local councillors. Such a model of devolving educational decision-making to bodies similar in nature to local authorities is used widely across northern Europe and north America, and is generally seen as successful (Hargreaves & Ainscow, 2015, p44). The governance proposals also included the setting up of six regional improvement collaboratives (RIC), umbrella bodies, each including several local authorities. This was modelled on the already existing Northern Alliance collaboration between the local authorities in the north of the country which had come together to cooperate on solving common problems such as the recruitment of teachers to remote and rural areas (Seith & Hepburn, 2017).

The imposition of RICs across the whole country by central government was controversial and met with widespread and vocal criticism. The Convention of Scottish Local Authorities, understandably, saw it as an attack on local authorities and that it would diminish significantly any local accountability for education in Scotland (Bryce & Humes, 2018a, p9). Others, such as Kier Bloomer, a former local authority chief executive, described the RICs as “top-down, authoritarian, unwanted and hierarchical” (Redford, 2018, p183), and would “reinforce all the worst characteristics of the culture of Scottish education” (Humes, Bryce, Gillies, & Kennedy, 2018, p975). The moves were seen by some as evidence of the centralising tendency of a government in power for an extended period of office with a relatively weak opposition, and which had already centralised other public services such as the police (Gillies, 2018b, p114). Others were more positive and saw the moves as an attempt to circumvent local authorities and free teachers and schools from their bureaucratic controls, where in some local authorities at least, headteachers had been treated as little more than ‘branch managers’ with local authorities ‘micro-managing’ and limiting school improvement (Bryce & Humes, 2018b, p47; Murphy, 2018, p293). Humes (1986) had previously commented on the centralising tendency of central government and the ineffectiveness of local government to either resist this trend or to really exercise effective local democracy in practice. He identified a situation where local councillors, lacking a good understanding of many of the issues involved, effectively hand over power to unelected officials who are more motivated with bureaucratic concerns than educational idealism. Humes goes on to state that “these officials, in pursuing their own interests, do not hesitate to treat their subordinates – not least classroom teachers – in a manner that frequency seems arrogant and contemptuous” (p107). Whilst this may not be a scenario existing in all local authorities, it is clearly not a culture that promotes transformative professionalism. The OECD, in its review of CfE, had criticised the governance of the implementation of CfE (McGinley, 2018, p187), and the gap between low and high performing local authorities (Bryce & Humes, 2018b, p50; OECD, 2015, p71). Priestley described the meso-levels of educational governance, largely local authorities and Education Scotland, to be risk averse in the face of accountability pressures resulting in incomplete engagement, strategic compliance, and performativity in relation to important developments such as the implementation of CfE (Priestley, 2018, p901).

It could be argued that the Scottish Government saw local government as a significant barrier to its policy implementation (McGinley, 2018, p187). The RICs also gave an opportunity for economies of scale and the potential to once again provide central support and advisory services which had been lost in the break-up of the regional councils into smaller local authorities in 1996, financial considerations continuing to be a significant policy driver. Local authorities, despite the variety of their modes of operation in different parts of the country, had generally received good inspection reports from Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Education (HMIE) and been seen as “positive forces for improvement” in Scottish education (McIlroy, 2018, p635). Therefore moves to diminish their role, along with a strengthened role for the national support agency, Education Scotland, were generally seen as “surprising” (Humes & Bryce, 2018, p120).

In addition to the introduction of the RICs there were four other main strands to the Scottish Government’s education governance reforms relating to almost all aspects of education including communities, teachers, headteachers, local government and national agencies. Consultation responses to these proposed education governance reforms, were mixed at best, quite negative in parts, and frequently sought greater clarity in the proposals, as exemplified by the statements made by Scotland’s national academy, the Royal Society of Edinburgh (Royal Society of Edinburgh, 2017, 2018a, 2018b). The independent research organisation tasked by the Scottish Government to collate the responses summarised the overall response as “In general, there was support for the principles behind the Education (Scotland) Bill although there was less support for legislation to enshrine these principles” (Why Research, 2018, p1). The Scottish Government’s initial response seemed to be to ignore much of the response to the public consultation, which in any case was described by McGinley (2018) as “The consultation appeared to be looking for answers to fit preconceived ideas to meet the political interpretation of the circumstances.” (p192). Rather than the legislation being passed by parliament and enacted, the Scottish Government was forced to roll-back its proposals and a consensus agreement was reached between central government, its agencies and the local authorities (Joint Steering Group, 2017; Scottish Government, 2018). This agreement, perhaps demonstrating the hegemony of the Scottish education leadership class, tempered the proposals but nevertheless resulted in the setting up of six RICs encompassing the 32 local authorities and the development of the Headteachers’ Charter but not the introduction of an Educational Workforce Council for Scotland to cover a wider range of education employees than that of the General Teaching Council for Scotland.

McIlroy (2018, p635) saw the governance review as an opportunity missed, and whilst its aspirations were worthwhile the focus on structures took away from a focus on changing culture and on teaching and learning. He saw both Education Scotland and the RICs compounding existing conflicts of interest and purpose, and adding to the churn which had constrained impact in recent years. He also saw a central government, far from empowering the profession, moving the Scottish education system further towards a centrally and politically managed one where that central government goes well beyond its democratic responsibilities to set broad priorities. Many would advocate that the fundamental problems with Scottish education are cultural rather than structural (Humes, Bryce, Gillies, & Kennedy, 2018, p975; Kennedy, 2008, p841), and as in the often quoted statement, allegedly made famous by Peter Drucker, “culture will eat strategy for breakfast”. The culture of Scottish education has deep seated roots which have encouraged teachers to be compliant and conformist in the face of the imposition of top-down policy (Bhattacharya, 2021; Humes, 1986). The educational landscape is complex and there have been a number of powerful agencies, interests, and competing voices jostling for influence (Murphy, 2018, p297). Therefore, despite politicians’ rhetoric of teacher and school empowerment and developing teachers as enquirers, many teachers have not been used to exercising their autonomy and engaging in independent critical thinking about important educational issues and demonstrating agency. That the subtitle of the Scottish Government’s governance review was “empowering our teachers, parents and communities to deliver excellence and equity for our children” (Scottish Government, 2017) does raise the questions of why teachers have been disempowered, and by whom, as well as what is required to fully empower them in practice. If they are to now be empowered, and the phrase is to be more than empty rhetoric, then Sachs’s trust, active trust, and generative politics (Sachs, 2003) must be allowed to develop through an improved culture of trust in teachers from politicians and system leaders. If teachers are to be able to attain any form of transformative professionalism which will have a truly transformative impact on both teachers’ individual professional growth, and on the performance of the education system as a whole, it will only be through such changes in governance culture.

Despite clear messages about a need for improvements in governance culture and a greater involvement of teachers and other education practitioners in policy making in more recent reports (Campbell & Harris, 2023; Muir, 2022; OECD, 2021) the Scottish Government ensured continued focus was placed instead on changing governance structures when, even before there was an opportunity to read and discuss the findings of the OECD review of CfE, it announced that as a result it was replacing the Scottish Qualifications Authority and reforming Education Scotland by splitting it into two separate organisations (Scottish Government, 2021c). Such an announcement may ensure that change can be seen to be occurring on the timescale of parliamentary terms but is likely to detract attention and effort away from the improvements in culture necessary for the longer-term improvement of education as a whole.

In addition to teacher professionalism, school leadership was, and continues to be, also identified as one of the six drivers for improvement in the National Improvement Framework (Scottish Government, 2016b). The emphasis on leadership has been a strong theme through the Scottish educational discourse of the 21st Century, and has been shown to be a significant factor both in school improvement and effective professional learning (Robinson et al., 2009), so this is explored further in the next section.

2.6 Teacher Leadership

The increased focus on business models of management in education since the 1990s has increased the emphasis on strong and effective leadership as a major plank of educational improvement, remaining so in the National Improvement Framework. School leadership was, and continues to be, the first of the six drivers listed (Scottish Government, 2016b, p10; 2021a, p25). Gillies (2018a, p94) argues that placing such an emphasis on leadership as the solution to educational improvement can involve an overly mechanistic and formulaic approach to what are actually complex social and relational problems. Traditionally the term ‘leadership’ has been associated with the hierarchical promoted post structures in schools, and the education system more widely. The GTCS introduced the Standards for Leadership and Management (GTCS, 2012b) specifically for middle and senior managers in schools, but in the Standard for Registration it also states that “all teachers should have opportunities to be leaders” (GTCS, 2012c, p2), plus the Donaldson Report included several recommendations on leadership, including one which resulted in the setting up of the Scottish College for Educational Leadership (SCEL). Partly due to the work of the Scottish College for Educational Leadership, and its successor (Education Scotland, 2020; Kelly, 2016), but also developments internationally (Frost, 2014; Harris & Muijs, 2005; Lieberman et al., 2017; Lovett, 2018), an increasing emphasis is now being placed on teacher leadership within Scottish education in addition to the more traditionally understood middle, senior, and system leaderships. Teacher leadership cuts across the traditional leadership hierarchies in schools and there are questions over whether teacher leadership does indeed add anything in addition to the transformative professionalism expected of all teachers, and with which there is significant overlap. In a meta-analysis investigating the association between teacher leadership and student achievement Shen et al. (2020) found that teacher leadership activities facilitating improvements in curriculum, instruction, and assessment were those most strongly associated with improvements in student achievement. It would appear this merely confirms that professional learning activities focussed on improving the core aspects of classroom teaching are the most effective at improving student outcomes rather than wider leadership activities. However, there is confusion around the concept of teacher leadership and Wenner and Campbell (2017), in a review of teacher leadership literature, describe it as “conceptually ill defined” and there is an unhelpful “muddiness” (p157) around the use of the term in both the research literature and its enactment in practice. In an national engagement exercise and survey on teacher leadership undertaken with over 1000 teachers across Scotland, Kelly (2016, p27) concluded “a cultural change in Scottish education is required to ensure that teacher professionalism and autonomy is equitably valued and nurtured across the system”. It appears that power relationships and hierarchy may still too often stifle the enactment of teacher leadership, and too few teachers in Scotland may yet identify sufficiently as teacher leaders for there to be a widespread culture of acceptance of teacher leadership, despite the prominence it has been given in policy to promote both bottom-up workforce reform and school improvement (Torrance & Humes, 2015). At the time of the McCormac report the chartered teacher scheme in Scotland was terminated, largely due to the tensions between its particular conception of individual autonomy and teacher professionalism and school and system leaders’ desire for accountability, evidence of impact, and need to allocate specific leadership duties to the post holders (McMahon, 2018, p863). Although progress may have been made, it appears there may still be some way to go for a culture which promotes effective teacher leadership, and/or transformative professionalism, consistently across Scotland’s schools as summarised by Torrance and Murphy (2017) following a study based on 45 teachers undertaking master-level leadership study at a Scottish university:

“Tensions between differing conceptualisations of teacher leadership, and its relationship to formal management hierarchies, run through both the literature and the experiences reported in this Scottish study. In the absence of a clear, coherent Scottish account of the concept and consequent practice implications of teacher leadership, the complicated interactions between formal and informal leadership expectations will continue to cause tensions in the relationships and practices of individual school communities.” (p41)

Having explored and described the Scottish educational policies as related to professional learning it is now important to consider the policy making process which had been used to produce these policies.

2.7 The Scottish policy style

Scotland is a small country with a population of just over 5 million people where the policy community, what has been described as the “leadership class” (Humes, 1986), is quite small and interconnected, and politicians are relatively accessible (Cairney & McGarvey, 2013, p159). With the transfer of responsibility for education from Westminster to Holyrood in 1999 the prominence of education in the Scottish political discourse was enhanced, and it was significant that the first Act of the new Scottish Parliament was on education (Gillies, 2018b, p108). However, education more generally is political in its wider sense, both in the creation and enactment of policy which involves an interplay between national politicians, local politicians, and a wide range of practitioners, often with competing priorities and agendas; even if all would claim their main aim is to improve the educations of the young people of Scotland. It is therefore important to try to identify the assumptions built in to the process and system, to unearth the power dynamics at play, and the hegemony which acts to retain the status quo (Brookfield, 2017). It can be argued that policy is very much a ‘process’ rather than a ‘thing’ (Adams, 2016) despite the widespread references to policy as the documents produced during the policymaking process. That process is fluid and messy rather than a linear process progressing from identifying a problem, to agreeing an policy solution, before implementing and enacting that solution in practice (Gillies, 2018a, p86).

The Scottish Parliament passes Acts on education relatively rarely, however, by 2018 it had passed thirteen statutes concerned with school education, plus numerous regulations, and much guidance producing what Scott (2018) describes as an “unwieldy hotchpotch” (p161). McGinley (2018) describes a situation since the advent of the Scottish Parliament where there has been an ongoing battle about the most appropriate governance structures for Scottish education where “Structures have been continuously changed in a piecemeal manner and without a full public debate” (p187), and Murphy (2018) states that “There can be no doubt that the present Scottish system of governance muddles and misaligns responsibilities and accountabilities at different leadership and management – school, middle tier and national-level agencies and officials” (p298). None of these descriptions paint a positive picture, so what is it about the ‘Scottish Policy Style’ that has made this so?

Prior to the devolution of responsibility for education to the Scottish Parliament policy making in Scottish education was described as being dominated by a relatively narrow “Leadership Class” (Humes, 1986; McPherson & Raab, 1988). This ‘inner circle’ consisting of senior civil servants, senior inspectors, senior office bearers in local authorities, and senior figures in teachers’ unions, in particular the Educational Institute of Scotland, and the Association of Directors of Education in Scotland would still appear to retain a considerable degree of narrative privilege in Scottish education policymaking and was described in 2015 as having “changed little since the 1960s” (Murphy & Raffe, 2015, p146). Midway through the first term of the Scottish Parliament, in the spring of 2002, a ‘National Debate’ on Scottish education was held. This did not consist of a typical consultation seeking responses to tightly set consultation questions but was more open with questions such as asking what people thought were the best and worst things about the current system. It was also aimed at developing policy in the medium term beyond the current and following terms of the Parliament, and encouraged people outside the normal policy community to respond (Munn et al., 2004). However, writing towards the end of the first term of the Scottish Parliament, Purdon (2003, p950) commented that a pattern was already emerging in the approach to education where there were public consultations on content and operation but no consultation on what the most appropriate approach should be in the first place. This implies a return to more a traditional approach to policy formation by the Scottish Executive and the use of less than truly open consultation processes seeking validation of a pre-determined policy direction. There is little evidence of this having changed since and often pre-consultation consultations have been used to shape and direct what then might then be described by some as an open consultation (Cairney & McGarvey, 2013, p162). This may well be the result of Scotland having a relatively small policy community where many of the key players belong to overlapping networks. Hutchinson (2018), drawing from the research of Ozga and colleagues (Clarke & Ozga, 2011; Ozga & Lawn, 2014), describes a situation in Scotland where policy makers, the inspectorate and senior teachers “occupy a partially shared milieu” (p208). This situation enables informal networking and the use of ‘back channels’ for communication between key players in the policy community outwith formal policy making fora (Humes, 2020). Whilst this relatively small policy community may well make it easier to reach the consensus that is generally a feature of Scottish education, and indeed Scottish politics in general (Cairney & McGarvey, 2013, p154), it may also be responsible for the development of ‘groupthink’, complacency, and a failure to question existing practice in a critical and fundamental manner (Humes & Bryce, 2018, p121). This may help explain the relative conservatism that is a common feature in Scottish education and the maintenance of a compliant, conformist, and in many quarters, dependency culture. That it is not uncommon for staff to move between Scottish Government, its national agencies, and local government is another likely driver for people to not want to step outside cultural norms resulting in inertia and reticence regarding fundamental change, and some complacent insularity (Bhattacharya, 2021; Humes, 2020; OECD, 2021, p87). It is in the interests of many of those in key positions of power to minimise fundamental change. One particularly poor example was when after the Scottish Education Council was set up in 2017, committee members were expected to have pre-meeting meetings with Scottish Government officials “apparently in an attempt to ensure that the formal meeting proceeded smoothly without embarrassing issues surfacing unexpectedly” but which resulted in the committee members feeling “that they were being steered away from ‘frank and open discussion’ towards an approved government line” (Humes, 2020). More recently, concerns about the recycling of senior staff within the delivery boards responsible for reform of their own organisations were raised (Seith, 2022a) but was nevertheless followed by the decision to reject key recommendations made in the previous independent reviews (Muir, 2022; OECD, 2021; Seith, 2022b). Hegemony clearly remains in action in Scottish education.

As can be seen from the descriptions of key reports above, a common policy creation strategy used by Scottish Government has been to set up an inquiry, chaired by a prominent member of the establishment, such as Graham Donaldson, former Her Majesty’s Senior Chief Inspector of Schools, and use the inquiry recommendations as a basis for its subsequent policy announcements. This process, given the small policy community in Scotland, can be open to the criticism that such inquiry committees draw their membership from a too narrow ‘leadership class’ of society, including lacking good representation of the teaching profession itself. This ‘leadership class’ may also communicate using too much jargon, and use consultations couched in such a way as to exclude those ‘not in the know’, a complaint made by the likes of parents’ groups (Connect, 2018). Those less well versed in the traditional processes of government and policymaking are likely to lack the knowledge and experience of how to best make their case, and issue identified by Munn et al. (2004, p449) in their analysis if the ‘National Debate’ which encouraged responses from a wider range of voices than other consultations. The outcome of such an inquiry process can also be particularly problematic when the Scottish Government quickly accepts the recommendations from the inquiry giving little time for parliamentary scrutiny or wider professional or societal debate, and hence also opportunities for political opposition. It could be argued that such a process has been at least partly responsible for the troubled implementation of CfE (Gillies, 2018b, p88).

Ministers obviously rely on other sources of advice beyond large and relatively infrequent inquiries. The role that Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Education has played in Scottish education policy creation is an important, and at times controversial one. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Education have always been shaped by the politics of the day, and in 2001, following the examinations crisis of 2000, for which they were largely, and some would argue unfairly, given the blame, they were made an executive agency of Scottish Government in order to place a greater distance been the two (McIlroy, 2013, p218). In what amounted to a U-turn this was reversed when, in a surprise announcement in 2010, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Education was amalgamated with Learning and Teaching Scotland to form the new ‘improvement agency’ Education Scotland, responsible for advice, support and inspection (McIlroy, 2013, p225), however, this situation is to be reversed once more (Scottish Government, 2021b). The Chief Executive of Education Scotland reports directly to the Cabinet Secretary for Education and having responsibility for curriculum advice and support, and inspecting its implementation in schools and local authorities, this gives Education Scotland significant narrative privilege within Scottish education. The work of the inspectorate remains influential on schools through its inspection and school self-evaluation framework How Good Is Our School? (Education Scotland, 2015) and its inspection reports (Shapira et al., 2021, p24) It is unfortunate that researchers in Scottish universities are little used to conduct independent research into important features of Scottish education, such as the implementation of CfE. There have been frequent calls for greater use of independent research, including as one of the recommendations of the OECD’s review (Gillies, 2018a, p90; OECD, 2015, p23; The Royal Society of Edinburgh, 2014, 2016). Many Education Scotland reports have no, or few, independent references, often only having circular references to other documents from the same organisation which opens Education Scotland to the accusation of presenting only its own form of ‘reality’, and as described by (Scott, 2000) of using “rhetoric and polemic under the guise of careful argument and empirical research” (p32).

Scrutiny of government legislation in parliament is done by its cross-party committees (Cairney & McGarvey, 2013, p155). There is evidence that there has been inadequate scrutiny in the past and the passing of poorly drafted legislation, such as when the UK Supreme Court ruled in favour of complainants and against the Scottish Government regarding the ‘named person’ legislation. However, more recently it appears that the Education and Skills Committee has taken a more robust stance in its meetings regularly questioning and taking evidence from senior figures in national agencies and the Cabinet Secretary for Education. This included calling for an independent review of the Senior Phase of CfE and which, after the Scottish Government lost a subsequent vote in the Scottish Parliament, was extended to the whole of CfE. Although it could be argued that by holding an independent review this removes the need for the Scottish Government to actually address the issues raised, at least in the short term. It appears that the Scottish Government is becoming more reactive and hasty in pushing through initiatives to official policy without adequate consultation based on an incomplete understanding of the complexity of the education system (Gillies, 2018b, p110). This may account for some of the ideological confusion exhibited in recent policies given it is subject to a range of stakeholders, networks, and pressure groups with access to the government in what has been called the “Scottish Policy Style” (Cairney & McGarvey, 2013, p154; Hulme & Kennedy, 2016, p93), and the whim of individual Ministers. This style is not necessarily unique to Scotland, or singular in form, and whilst there is evidence that the majority are satisfied with the process and think that their views are listened to (Cairney & McGarvey, 2013, p169), whether they actually have significant influence on change is more debatable with civil servants frequently acting as gatekeepers to Ministers (Cairney & McGarvey, 2013, p160). However, there is also evidence that members of the teaching profession itself do not feel sufficiently consulted on the very issues on they have most experience and expertise; school education, including on their own professional learning for both personal growth and system improvement (McIlroy, 2018, p625).

2.8 The involvement of teachers in policymaking

The research of Kraft and Papay (2014) and Kini and Podolsky (2016) show that when teachers feel that they are working in a supportive environment in which they can demonstrate agency through having both good levels of autonomy whilst belonging to a collegiate culture, this increases their job satisfaction, desire to remain in post, and importantly improves pupil outcomes. Others might describe such an environment as one which promotes transformative professionalism, and one which leads to system improvement. The reverse of this situation is one where teachers do not feel that they have opportunities to influence their environment, including the policies applying to their practice, with corresponding lack of positive impact on outcomes. In such situations Netolicky (2019, p8) describes teachers becoming “the objects of policy” or “pawns used in games of politics”. Even if there are opportunities for the teacher voice, if the prevailing culture is one of top-down power hierarchies, teachers may be wary of speaking truth to power, and there are indications of this being the case in Scottish education, exacerbated by restrictions on engagement in policy discussion in teachers’ employment contracts (Murphy & Raffe, 2015, p154). The lack of a teacher voice in educational policymaking, and time for teachers to make meaning out of policy change, as a barrier to the enaction of change has been well recognised for some time (Fullan, 1991, p112). In recent years in Scottish secondary schools there is ample evidence that many teachers have felt that their voices have not been heard during the policymaking and policy-enacting phases for significant issues such as CfE, Senior Phase curriculum architecture, Scottish Qualification Authority (SQA) assessment design, and related workload issues. This has included responses to surveys by professional associations (EIS, 2013, 2014; SSTA, 2019), in submissions to the inquiries of the Scottish Parliament Education and Skills Committee (Scottish Parliament, n.d.), in the GTCS review of the first five years of professional update (GTCS, 2020), and in the reviews and consultations following the 2021 OECD review of CfE (Campbell & Harris, 2023, p57; Muir, 2022, p15). Gillies (2018b, p109), with the benefit of hindsight, provides a quite pointed critique of the somewhat chequered enactment of what is arguably the most significant Scottish educational policy of the last two decades, CfE, particularly in secondary schools. He points the finger at the lack of involvement and engagement of teachers at all of the key stages as the root cause. In the words of Bryce and Humes (2018b) “tensions … can exist between officialdom and classroom teachers when changes are being introduced” (p52), and they ask that in the future in Scotland “Their [teachers’] voices need to be heard, not as a token gesture during carefully managed ‘consultation’ exercises, but as a regular part of their professional work, contributing to the evolution and improvement of the system as a whole” (p54). A similar call is made by Kennedy and Beck in relation to teacher professional learning in Scotland. They ask that “this should not be a discussion which exists only among senior policymakers, it must include teachers and the wider education community in talking together about what constitutes valuable and worthwhile professional learning, and how we might best account for our actions in this sphere” (Kennedy & Beck, 2018, p856)